CHY4U

World History Since the Fifteenth Century

Unit 1: 1450 - 1650: What Were They Thinking?

Activity 1: Introduction to Historical Thinking and Inquiry

When your History teacher was in school, history was probably taught in the way that Michael Scott describes. Students in Canada learned about North America and Europe, certainly, but little else; in fact, there is a good chance they never left those continents. If you had siblings who took a senior history course, they may have had a slightly different experience. They may have examined South America in the 1500s, or learned something about India and China in the 19th century. Examinations of these regions were often Eurocentric: regions from other parts of the world were only studied because of their relationship to European powers.

|

This course, however, is different. Its title, World History Since the Fifteenth Century, reflects a new focus: global history. You will examine a variety of regions and cultures over five hundred years. While several societies figure prominently in a few units, there will also be civilizations that we examine only once. We hope that this approach will provide you with the understanding of history that is truly global. We will also be examining how history is constructed by analysing previously written historical texts. This is called historiography. |

We also hope that this approach will help you answer the question “How Did We Get Here?”

Throughout the course you will be asked to reflect on the course question by adding to your Portfolio.

How Did We Get Here?

How Did We Get Here?

Please respond to the following questions:

- How does historian Michael Scott say we have answered this question before? Why is this version of our “story” problematic?

- What parts of the question will you need to define to be able to answer it?

- What factors might lead to different responses to the course question by the other students in this course?

Your learning throughout the course will be anchored by the Historical Thinking Concepts. While you may remember these concepts from a previous history course, it is important to review them now. They are key to the study of history, and make “historical thinking” possible:

How did Japan change?

How did Japan change?

Before we move on to the remaining foundations of Historical Thinking, let’s review the ones we have already considered.

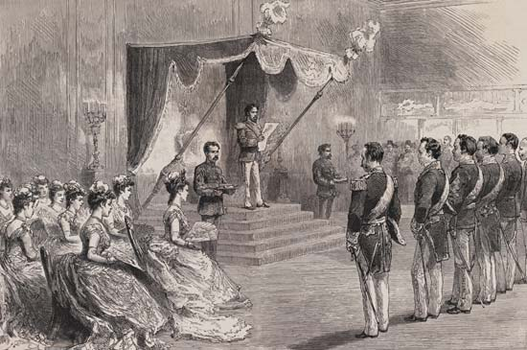

Earlier in this activity, you briefly examined a picture depicting the announcement of the Meiji Constitution in 1890, which we know now was a turning point in Japan. Now consider this drawing, from an 1860 reception at the White House. The President of the United States is receiving a Japanese delegation. The delegation is in traditional Japanese garb; the men on the left and the party goers behind them are in western clothes.

Question: What can you infer about how Japan was changing based on the differences in clothing?

Citizenship Education

Many people enjoy stories from the past, whether you read them in books, play historical video games, watch documentaries, listen to storytellers, or visit museums and other historic sites. These can be entertaining and educational, but if we are to truly become historians, we understand that we study history to understand ourselves, the power and systems in our own societies, to develop a sense of personal identity, to understand the ideal and not-so-ideal attributes and character traits of citizens, and ultimately, to become actors in our own societies, to create histories that will be meaningful to us and our communities. Just like societies today, societies of the past were complex. Not everyone agrees about how to remember our past, but it is clear that how we remember it, who we choose to remember and how we choose to present history, both reflects and shapes our views today. When we investigate controversial issues of the past we are actively using the ethical dimensions of history and learning to become active citizens in today’s world.

A historian’s work is really the decoding and analysis of primary source evidence. A primary source is a piece of evidence from an era that can be used by historians to understand that specific era. Primary sources come in many forms, including government documents, personal belongings, and anything else from the time (such as the Codex Mendoza). In contrast, a secondary source is written after the fact, and is about and after the time; for example, the painting by Leutze we considered earlier is a secondary source. Secondary sources, like museum displays, textbooks and documentaries feature analysis by historians who tell the reader/viewer what matters. While such sources can be invaluable, they also do some of the work for us; in this course, while we will examine some secondary sources, we will focus on doing the work of the historian, which means that we must use primary source documents to reach our own conclusions.

Classifying sources, however, isn’t always easy. For example, let’s imagine that we are examining a book written in 1936 about World War I. In one sense it is definitely a secondary source; it was written over a decade after the war, and it is designed to examine the past. On the other hand, historians examining bias and values in the 1930s could argue that the text is a primary source, too; such a book might provide insights into how events of the 1930s—such as the Great Depression and the rise of Fascism—were impacting historians’ work.

Before we proceed, we need to practice identifying primary and secondary sources. The first few options have been identified for you, but you will have to classify the last few sources. Don’t worry; this quiz is only a diagnostic. It is designed to help you become more adept at identifying the differences between primary and secondary sources.

In this activity you learned about:

- the course overarching question, and answered 3 related questions to help you frame your understanding;

- the historical thinking concepts;

- primary and secondary sources.

How Did We Get Here?

How Did We Get Here?

Reflection

- Craft a reflective response in which you briefly explain the connection between one of the Historical Thinking Concepts and one of the primary or secondary sources from the previous learning object. For example, you could explain how one of the sources reflects Cause and Consequence, or how another seems to connect to Historical Perspective.

- Because it is important to acknowledge sources for our work, explicitly mention the author/creator. An effective way to do this is to follow the author’s name with a verb of attribution. For example, we can write something like “Malcolm X argues that” or “Kinew asserts that” to introduce an important idea that the author espouses.

- Provide a citation that fully documents where you found your information. You will notice that each source above contains a link to the original. While you are not responsible for reading the content on the original page, you are responsible for citing the information properly.

For your reference: