CLN4U

Canadian and International Law

Unit 4: Issues in Criminal Law

Activity 1: How Long is the Arm of the Law?

By SimonP (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Imagine that one night you make a choice to vandalise a local cemetery. You are spotted by neighbours who call the police and the act is caught on video surveillance cameras. Two days later; following a brief investigation, you are charged by the police. All kinds of questions would be running through your mind: What are the charges? How does the court process work? What are possible penalties?

In this case the charge against you might be mischief. Read the following section from the Criminal Code.

430 (1) Every one commits mischief who wilfully

- (a) destroys or damages property;

- (b) renders property dangerous, useless, inoperative or ineffective;

- (c) obstructs, interrupts or interferes with the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property; or

- (d) obstructs, interrupts or interferes with any person in the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property.

The police inform you of your legal rights and you, with the help of your parents, retain a lawyer. The lawyer explains that the possible punishments are also written in the Criminal Code. She explains that the judge has discretion during the sentencing. Here is what you find out from your lawyer:

Punishment

(2) Every one who commits mischief that causes actual danger to life is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for life.

Punishment

(3) Every one who commits mischief in relation to property that is a testamentary instrument or the value of which exceeds five thousand dollars.

- (a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years; or

- (b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Idem

(4) Every one who commits mischief in relation to property, other than property described in subsection (3),

- (a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

- (b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Mischief relating to religious property

(4.1) Every one who commits mischief in relation to property that is a building, structure or part thereof that is primarily used for religious worship, including a church, mosque, synagogue or temple, or an object associated with religious worship located in or on the grounds of such a building or structure, or a cemetery, if the commission of the mischief is motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on religion, race, colour or national or ethnic origin,

- (a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years; or

- (b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding eighteen months.

“Oh, oh!” The seriousness of your legal trouble is becoming evident. Fortunately no one was in danger when you were destroying parts of the cemetery; this is your first offence; you are under the age of 18, and you are willing to accept responsibility for your actions. However, the property that was destroyed will be very expensive to repair and there are serious concerns about your motivations for your actions. The authorities wonder: Were the headstones specifically targeted due to race or religion? In the end, the Crown Attorney proceeds with a summary offence charge.

You go before a judge to enter your plea of “guilty.” Your lawyer tells you clearly that a guilty plea cannot be changed later and that you are giving up your right to have a trial. The judge also reminds you of these facts. The judge will make sure you understand the charges and the consequences of a guilty plea. In this case, you may return at a later date for the judge to sentence you. The judge would weigh the various factors and might determine a sentence of community service, a fine and perhaps a probationary period.

Your fictional criminal offence is quite straightforward. In Canada, it is quite easy to learn about specific laws.

- Penalties for breaking the law are articulated within the law itself.

- The content of our laws is available to everyone; each of us is expected to abide by the laws. The laws are written down (in the Constitution or Criminal Code for example). An individual cannot choose whether or not to follow a particular law.

- The laws are created by a democratically elected Parliament or Legislature.

- We have a police force that investigates crimes and enforces the law.

- The judicial branch ensures that you have a fair trial.

Now, imagine this scenario on an international scale. The cemetery in question belonged to a minority group that had been a target of government persecution and violence. The cemetery was sacred ground for religious and cultural reasons. The damage was committed by a large group of individuals at the order of a leader. While the basic act is similar, there are tremendous differences. How might the law handle this situation?

You might wonder:

- Can the country in question hold the people responsible? If not, are there international laws that can help?

- If it is the state power who is targeting a group of people, what recourse do they have to achieve justice?

- Who or what institution made the laws? What are the sources of the laws?

- Does every state agree to follow the laws? To whom do the laws apply?

- Who will enforce the laws internationally?

- If an individual is held responsible, who will determine guilt or innocence?

- Will the individuals responsible recognize the authority of the court?

Think about the questions above as you hear about a decision made by the International Criminal Court in August of 2016. This case centres upon the intentional destruction of cultural monuments by extremists in Mali.

What big ideas emerge in this video?

- The destruction of cultural heritage is considered a war crime. This was established by the Rome Statute.

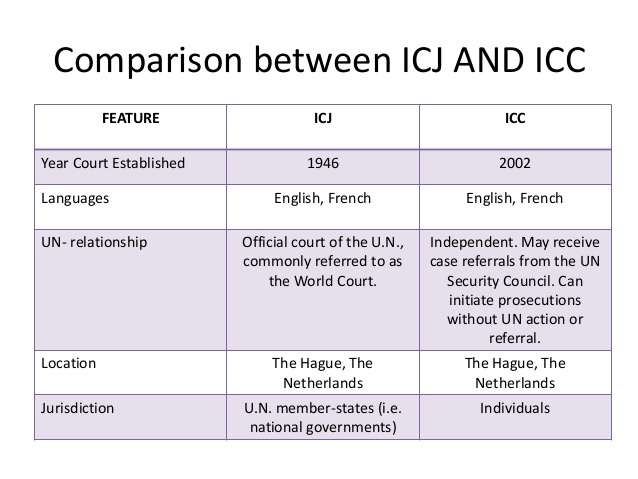

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) can arbitrate disputes and pass judgement.

- Not every country is subject to the jurisdiction of the ICC.

- Countries have to sign and ratify an agreement in order to be held accountable by a particular international law, such as the Rome Statute.

- States have to comply with the law and assist the ICC in order for people to be brought to trial as there is no international police force.

- A determination of guilt requires evidence in international law.

- Military necessity can be an accepted reason for the destruction of cultural property.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court often referred to as the International Criminal Court Statute or the Rome Statute is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome on 17 July 1998 and it entered into force on 1 July 2002.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) investigates and, where warranted, tries individuals charged with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Court aims to hold those responsible accountable for their crimes and to help prevent these crimes from happening again. As a court of last resort, it seeks to complement, not replace, national Courts. Governed by an international treaty called the Rome Statute, the ICC is the world’s first permanent international criminal court. Source

Clearly the scale of the crime and the influencing factors are vastly different but what is of interest to you at this point are some of the differences and similarities between domestic and international systems of law. The laws are created, enforced and adjudicated differently. The case presented above helps you to begin to answer some of the questions. Please watch "International Law Explained" for a brief introduction that will also address some of your questions.

Sources of Law

You know that laws are rooted in our historical and religious traditions. They are linked to philosophical thought and political theory. Laws are closely connected to cultural beliefs and they change over time in response to shifting morals and values. Media, political climate, national emergencies, technology are among the many factors that influence or change law over time.

Understanding the roots of law and the many influences on legal change helps us to understand the differences in the legal systems and in the domestic laws of different countries. Think about the differences that exist among countries such as Somalia, Egypt, Indonesia, Australia, the Netherlands and the United States! In just a small sampling of countries you can see incredible diversity of cultural beliefs and practices, religious traditions, geographical or economic realities, as well as national history.

Surprising Differences

Surprising Differences

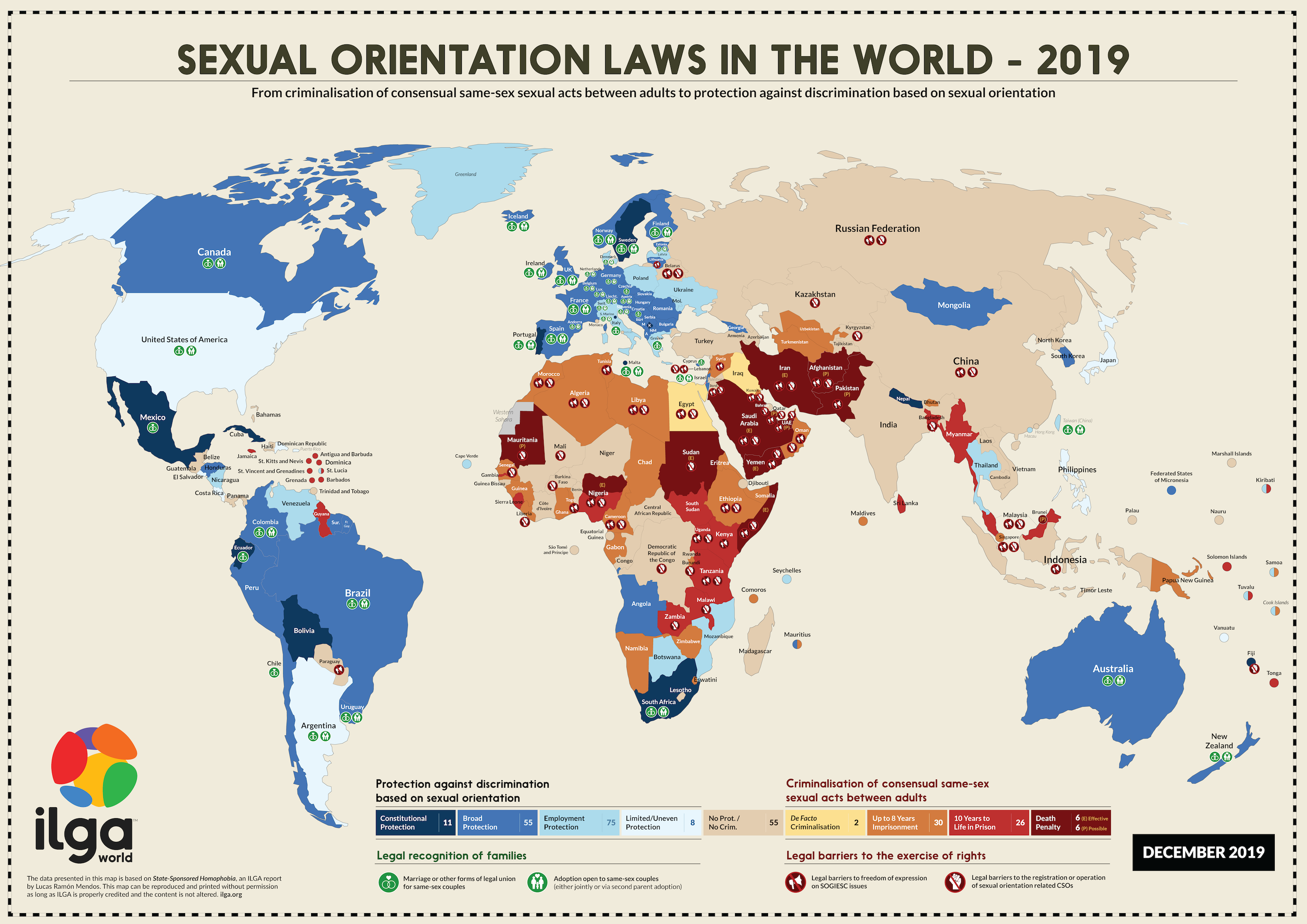

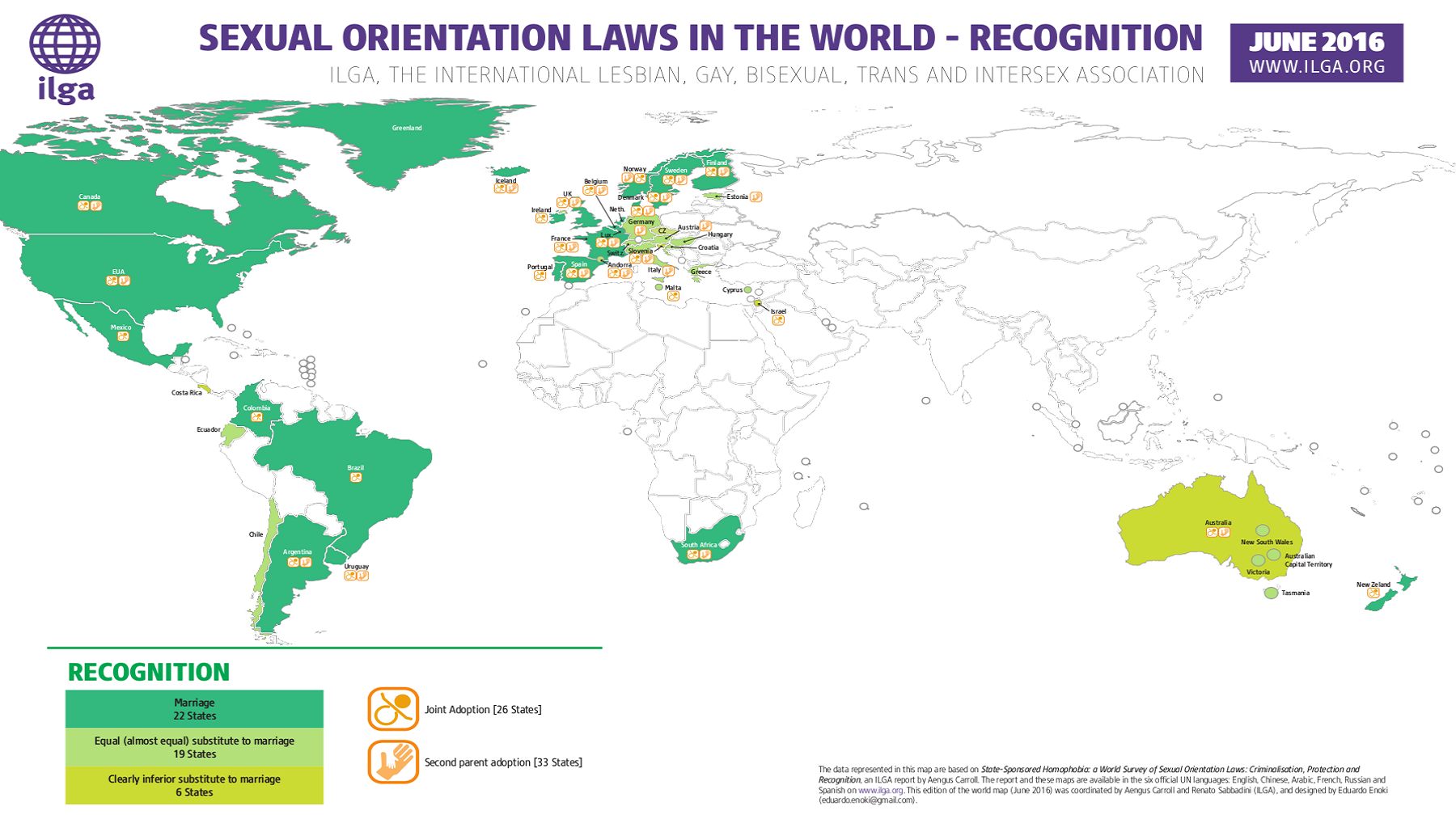

One area of law that can illustrate the differences among countries are laws pertaining to sexual orientation around the world. Look at each of the visuals below. There are four maps to inspect:

- Overview;

- Criminalization;

- Protection;

- Recognition.

Please take some time to view each map carefully.

Think:

- Why do you think the laws differ so much?

- What surprises you?

- What observations can you make?

- What questions do you have?

Consider the tremendous differences among states and you can see the challenges that emerge when those same countries try to come to an agreement. If you have done an activity with a large group of people lately, you will know that it is difficult to make a decision that meets the needs of every member of the group. If you can’t decide which ride to go on as a group at an amusement park, imagine the difficulty in coming to an agreement about climate change, human rights or international criminal acts!

If the countries are so different, where do international laws originate? What are the sources of international law?

Despite the many differences among countries, there are shared experiences, values and beliefs, as well as goals that unify the international community. These form the impetus to create international law. Countries sign treaties to facilitate trade, protect a waterway or address child slavery for example. Customs that many countries practice have attained legal status over time and there are certain principles in which most states believe. In addition, the world relies upon academic research and court findings to guide legal thinking.

Take a peek at Sources of International Law Explained for a brief introduction.

Tips

Yikes! There were new words in there and it was written in a formal, legal manner. What did you do when you came across an unfamiliar term or a complex sentence? It is very normal to read material twice or three times when you are working at the university level. Remember - "google" is a verb; an action word. Look it up if you need to clarify a concept or definition. It does take time but expanding your vocabulary can be fun - it gives you more choices and it will help you to refine your writing and speaking tasks.

Before you move on...do you know the meaning of the following terms?

- pacta sunt servanda

- comity

- immunity

- inviolable

- innocent passage

- jurisdiction

- high seas

- non-combatant

- reparation

- subsidiary means

If you are comfortable using all of the words above in a sentence, it is time to move on. Take a moment to ensure your own understanding.

International law is the law that governs the relations between or among nations. It is complex:

- There are laws to cover the areas we share: space, the ocean water and the sea beds as well as the polar regions.

- Laws exist to promote and protect human rights, health, education, food, the environment and labour conditions.

- There are bodies of laws to govern our economic interactions such as trade agreements, financial transactions, investments and property.

- There are laws relating to war, peace and security.

- There are also laws that articulate how disputes will be settled and the principles upon which the world community can agree.

Among many other tribunals and peaceful methods of dispute resolution, there are two judicial bodies or courts that hold States and individuals accountable for their actions. It was a treaty; known as the Rome Statute, that established a permanent International Criminal Court. The International Court of Justice is the primary court of the United Nations that was also created by a treaty when the UN was founded. Member countries signed the Charter and by doing so, agreed to the jurisdiction of the court.