EWC4U

Unit 1: The Writer’s Toolbox

Activity 4: Planning Perspective’s Purpose

If you tell the reader that Bull Beezley is a brutal-faced, loose-lipped bully, with snake’s blood in his veins, the reader’s reaction may be, ‘Oh, yeah!’ But if you show the reader Bull Beezley raking the bloodied flanks of his weary, sweat-encrusted pony, and flogging the tottering, red-eyed animal with a quirt, or have him booting in the protruding ribs of a starved mongrel and, boy, the reader believes!

a short-handled riding whip with a braided leather lash.

Did You Know?

Did You Know?

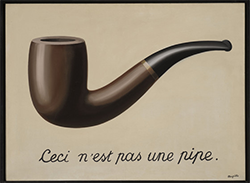

Then what is it...?

LACMA

Surrealist painter René Magritte’s famous painting is called The Treachery of Images. The French phrase at the bottom of the painting translates to ‘this is not a pipe.’ If that’s true, then what is it? More importantly, what is Magritte trying to say with his provocative painting?

If you had been told, "this may be the most ‘meta’ Did You Know" yet, you would be primed for how to view the image, and what to expect. In many instances, that can be useful since such primers guide and direct you toward the intended outcome.

Then again, there are times when not knowing the purpose can be exciting, even exhilarating. After all, why does it seem so wrong to read the last page of a mystery first?

There are many philosophers who argue that perspective is everything. As a writer, how you develop that perspective is determined not only by your choices (plot, characters, setting, theme, dialogue, voice, style, genre, medium, etc), but also by your own personal worldview. Simply, whether they realize it or not, embrace or it or rebel against it, writers write what they know and believe.

However, it’s important to remember that, as we expand our worldview and our perspectives broaden, our writing tools grow along with them.

Writer’s Notebook

Writer’s Notebook

In keeping with the idea of perspective and choice, you have three different options that may challenge your current worldview: a video, a reading and a comic. You can chose one, two, or all three. After viewing, think about how this new knowledge affected you on both a reasoning and emotional level, and how both it - and those reflected realizations - can influence your own writing. Then, record your thoughts in your Writer’s Notebook so they aren’t forgotten.

Throughout this course you will keep an electronic and/or paper notebook on you at all times (even by your bedside!). It will be helpful for ensuring you don’t forget a great idea, turn-of-phrase, character name, etc, and it will illustrate your growth as a writer too!

Show, Don’t Tell

Remember show and tell? Is it fair to say that it’s likely that the telling part made up a lot more of the presentation than the the showing aspect? And yet, wasn’t it the showing that was the most interesting part? Throughout this activity you will learn about and then experiment with, three important writing techniques which will enhance your personal writing.

Well, in writing it’s exactly the same. One of the most important tools that a writer can develop is the ability to show the reader rather than tell her or him what’s occurring. Of course, this is easier said than done (which is exactly the point)! Famed author, Ernest Hemingway, coined the term ‘Iceberg Theory’ to describe his style of showing rather than telling. Here are his ideas in his own words:

Sometimes what you don’t see

is the most important part...

WikimediaIf a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.

In essence, showing rather than telling involves selecting, using, and occasionally combining a variety of tools to craft a more engaging, involving narrative. Throughout this activity, you will learn more about crafting characters and picking proper points-of-view.

However, not every author agrees that showing should always be used at the expense of telling. Consider the following opinion:

Sometimes a writer tells as a shortcut, to move quickly to the meaty part of the story or scene. Showing is essentially about making scenes vivid. If you try to do it constantly, the parts that are supposed to stand out won't, and your readers will get exhausted.

Show and/or Tell?

Show and/or Tell?

Research different ways to show and tell. To get you started, there are resources listed below, but you should also conduct your own research, as well. Also include your opinion about the following question: is it better to show and/or tell, to what degree, and where and when?

Showing and Telling Reference Chart

Showing and Telling Reference Chart

After you are finished, design a reference chart that allows you to use showing versus telling effectively. For example:

- don't tell what a character is feeling, rather let her or his actions convey feelings;

- use dialogue to show rather than tell;

- if something is trivial, it's good to tell; and

- don't overuse show versus tell, as it will lose its effectiveness.

Resources

- Writing Tutorials - #12 Show, Don't Tell! is an informative video explaining the reasons for showing instead of telling.

- How to “Show Don’t Tell" provides clear examples of both occurring in writing.

- Show, Don’t Tell provides four points with examples for how to write well.

- “On Writing”: Show, Don’t Tell is an excellent article by Hugo and Nebula award winning science-fiction author Robert J. Sawyer on how to show in your writing.

- This Itch of Writing: The Blog is a clear and thorough account of how and why adopting a showing style is effective in writing.

Enrichment

Enrichment

Rush says it best: “[Y]ou can twist perception. Reality won't budge!”

Wikipedia

The idea of show, don’t tell isn’t limited to writing. Hear it put into practice by listening to Rush’s epic song Show, Don’t Tell or reading the lyrics!

Crafting Characters

Remember: Plot is no more than footprints left in the snow after your characters have run by on their way to incredible destinations.

Throughout this course, you will craft a variety of characters. Before beginning, it’s important to review some key concepts and strategies to ensure that you are creating the right character for your narrative.

Whether your character is human, an animal, or a robot, the plot of your story centres on your character and how events affect him, her or even, it. Your character's actions and words will define and drive your narrative. Thus, when you create your fiction, you need to develop believable characters that can carry your plot and engage your reader.

Writer’s Notebook

Writer’s Notebook

When creating characters you need to keep the following important points in mind:

Characters want something – in other words, if your character doesn't have a motivating goal then you don't have a plot.

Characters need to be realistic – even if your story is science fiction or fantasy, your characters still need to feel and sound realistic or your reader will not accept them.

Characters are (usually) imperfect – if your characters are realistic then, like real people, they have to have imperfections and flaws. Remember that characters who try to achieve their goals while being hindered with the burden of “humanness” are what will keep your reader engaged.

Characters are (usually) sympathetic – because your characters have their flaws, your reader can sympathize and empathize with them. If you can get your readers excited, or bring them to tears because they care about your characters, then you have succeeded in your character’s development.

It’s recommended that you copy this into your Writer’s Notebook for future reference and use.

In fiction, there are certain common character types. You are probably familiar with all of them, either from the stories that you've read, or the films and TV you have watched. In this interactive activity, you will have a chance to learn about different character types. If you're working on a tablet, click here to open the following interactive in its own window instead of using the embedded version below.

Crafting Characteristics

Crafting Characteristics

Now that you've studied different character types, select a prompt from your Writer's Notebook (you did this in Unit 1, Activity 2) then complete this Crafting Characters template to create some of your own for use later in the activity.

Picking a Point-of-View

Earlier in this activity, you learned the importance of perspective. Well, in addition to crafting characters, a writer needs to determine from which point-of-view the story will be told. The lens through which you tell your story can be as narrow as that from a single perspective or as broad as being all-seeing. Your story’s narrative will be dramatically different no matter which option you chose.

How does your point-of-view change if you decide to look through the telescope instead of over the railing?

What follows is a short review of the typical points-of-view available to you as a writer.

First Person Point-of-view

The first person point-of-view uses pronouns (I, me, my, we, us, our) to tell the story. It can be further subdivided into two types:

- the narrator as a major character who tells the story; often this story is chiefly about the narrator; or

- the narrator as a minor character who tells the story that focuses on someone else; the narrator is still a character in the story.

Second Person Point-of-view

In second person point-of-view the story is told using "you," the second person pronoun.

Third Person Point-of-view

This point-of-view tells the story from the vantage point of the third person pronoun - he, she, it or they. There are two main kinds:

- limited or objective third person point-of-view; or

- omniscient third person point-of-view.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

Oh, hello. I didn’t see you there...

Hey there EWC4U student, how’s it going? Are you finding this activity useful and engaging? I hope the information that you are introduced to here will assist you in your writing. Lastly, isn’t my dog Desdemona (Desi for short) ridiculously cute? She’s named after the iconic character from Shakespeare’s Othello.

The commentary above is an example of breaking the fourth wall; that is, even though you know that this course was written by someone (in this case, a team of educators), we never address you directly. In stories, this occurs when a character acknowledges their fictionality, by either indirectly or directly addressing the audience. It can be a stylistic technique to engage the audience, though it is not without its share of critics. One of my favourite movies that breaks the fourth wall is Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. What movies can you name use this perspective? And now, back to your regularly scheduled course...

What’s Your POV?

What’s Your POV?

It’s important to remember that there isn’t a “better” option; instead, the important question you need to ask yourself is: ‘why are you choosing that perspective?’ To help you with this essential question, develop responses to the following points:

- two advantages and two disadvantages for each point-of-view;

- when and why you’d be most likely to use each of the three points-of-view in your writing; and

- an example of each of the three points-of-view being used (ideally in stories that you would recommend). Be sure to include the proper MLA attribution.

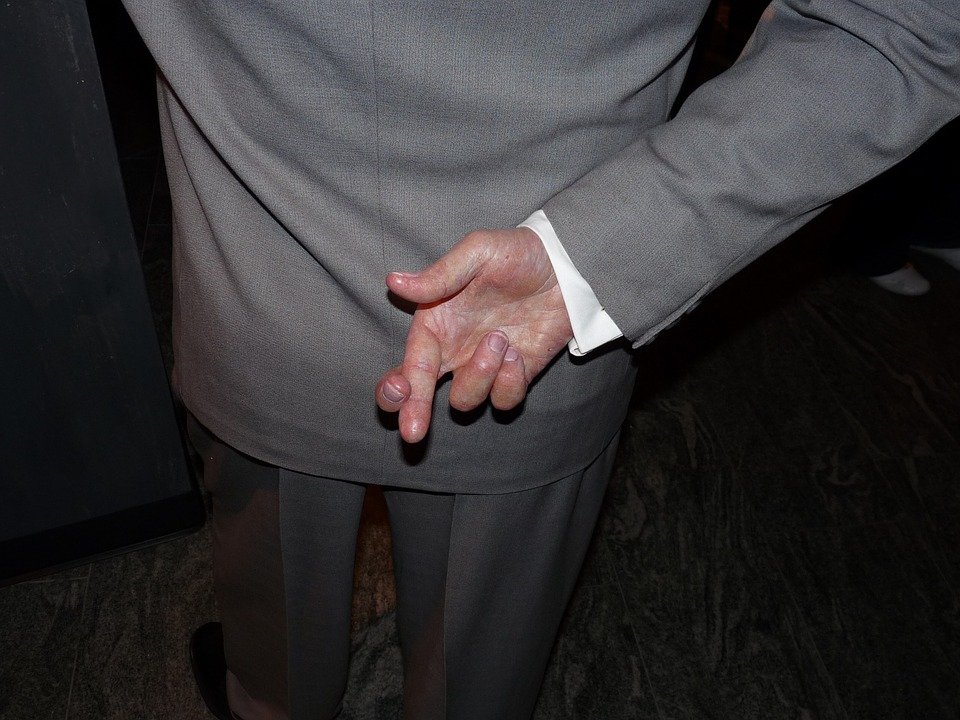

“Trust Me…”: The Unreliable Narrator

Not all narrators are reliable. While you as writer likely know all of their inner thoughts and motivations and external decisions and outcomes, that doesn’t mean the reader needs to trust them. Since they are unreliable narrators, the reader comes to recognize them as characters who cannot be trusted because their interpretations of incidents or individuals do not coincide with what really happened. Often the hallmark of this kind of narration is that it is from a flawed and distorted perspective.

On average, people lie ten times a week.

The narrator is incapable of seeing things as they really are; it is left for the reader to see beyond the narrator to the truth. The unreliable narrator can be either first, second, or third person in nature.

Here are some famous examples, all of which are well worth reading:

- the narrator of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange;

- the narrator of Daniel Keyes' Flowers for Algernon;

- Margaret Atwood's main character in Alias Grace; and

- Mordecai Richler's main character in Barney's Version.

Life Happens (And sometimes it doesn’t)...

It’s not unusual for writers to become attached to their characters - sometimes to a point where the writer is unwilling to present these characters with opportunities or challenges that will change them. However, as the cliché goes, ‘life happens,’ and, sadly, sometimes in ways that are unexpected, undesired, or unwanted.

Sometimes there’s only one choice...

As a writer, you should not be afraid to make hard choices if it means a more engaging, involving, realistic, or desirable story. Having said that, a writer needs to decide whether her or his characters have accomplished everything set out for them to do; killing off a character too early can result in an underdeveloped narrative!

Fans of the sci-fi show Babylon 5, are aware that the main character and protagonist, John Sheridan, was beloved by his creator, J. Michael Straczynski. However, as a writer willing to make hard choices, Straczynski knew that Sheridan’s death was necessary for the narrative to be complete. To give him a fitting send off, he had this final exchange:

Sheridan: "There is .. so much I still don't understand."

Lorien: "As it should be."

Sheridan: "Can I come back?"

Lorien: "No. This journey has ended. Another begins. Time .. to rest now."

Show and Tell Time!

Show and Tell Time!

Now that you’ve learned the difference between showing and telling, it’s time to put theory into practice. Select any of the options from the list below. For your choice, write a 500 to 1000 word short story that ‘tells’ the reader what is happening followed by another short story where you ‘show’ your reader what is going on.

- Community event/celebration

- Robbery

- Aliens Arrive

- First Date

- Historical or current event

- Olympics

- Citizenship Ceremony

- Taking a Risk

- Canoeing

- Shopping

After writing your short stories, you will write a short paragraph explaining what writing choices you made for the telling and the showing stories. Make sure you explicitly show your knowledge of the criteria (refer to your reference chart) of how to apply this technique.

Character Sketch

Character Sketch

Now that you’ve had a chance to craft a company of characters’ outlines, it’s time to flesh them out. In addition to your main character, select any three characters (for a total of four) and write an approximately one hundred word paragraph that describes your character doing something simple (e.g., brushing teeth, getting dressed, shaving, applying makeup). People's personalities are revealed in the way they do simple things. Remember: don’t tell us how the action is done - show us.

Next, write several lines of dialogue (at least ten sentences in total) in the character's voice responding to the following questions:

- After listening to a confidante, how would your character respond to the question, “So that’s my deepest, darkest secret...what’s yours?”

- Just before leaving home, how would your character respond to a person who asks, "Are you sure you’re ready?"

- After arriving home at 3:00 a.m., how does your character respond to being asked, "Where have you been all this time?"

Make sure you show that you’ve understood the provided criteria for crafting characters and using point-of-view.

Metacognitive Moment

Metacognitive Moment

This activity began with a ‘meta’ perspective, and so it seems fitting that it should end that way, too. After completing the Character Sketch assignment, write a short ten question-and-answer interview with the author….YOU! Be sure that your questions and answers allow you to share what you’ve learned about your growth as a writer, including specific references to what you’ve learned throughout this activity. Be as specific as possible.

Enrichment

Enrichment

A long-standing writers’ strategy is to read their work out loud. Hearing the words allows you another opportunity to assess word choice, punctuation, pacing, purpose, and intent. So why not try this for yourself? Record your characters’ dialogue and/or interview; try to adopt the speech patterns (volume, tone, pacing and pronunciation) you would expect them to speak.

If you want to view any links in these pdfs, right click and select "Open Link in New Tab" to avoid leaving this page.