How do We Know What We Know: Exploring Epistemology

The Origins of Knowledge and Truth

MINDS ON

“

The earth is supported by the power of truth, it is the power of truth that makes the sun shine and the winds blow, indeed all things rest upon truth.

~ Chanakya, Indian Teacher and Philosopher (350-275 BCE)

What is Truth?

Defining "truth" is complex, even though on the surface it seems self-evident. We can say that truth is a statement about the way the world actually is - yet, even a statement such as this is open to challenge. In fact, such a statement would lead some to question how we understand and define the world. Consider Descartes, for example, who questions perception, itself.

So, how do we know what ‘truth’ is?

Consider the following idea. We understand that someone who knowingly speaks falsely is lying, but, what if this individual does not believe they are speaking falsely? What if this person is wholly convinced that what they are saying is true and believes that what you are saying is false? What if it is true in her/his mind, then what of the 'truth' in your mind?

Truth from Falsehood

Truth from Falsehood

Create a T-Chart. For this purpose, you may use a word processing program such as Microsoft Word, Google Docs or simply write your T-Chart on a piece of paper.

On one side of the chart, write down ten things that you know to be true; on the other side of the chart, write ten things you know to be false.

Now, explain why, as follows:

- Provide two or three reasons or pieces of evidence to support why you ‘know’ these things to be true or false.

- Once your True/False Chart is complete, reflect on the system that you applied to determine truth and falsehood.

- Prepare a general statement that outlines the limits of what you can know, do know, and how you know it.

- Prepare three questions you could generally use to determine truth or falsehood.

Epistemology

Epistemology

In Epistemology, we seek to understand what truth is. Indeed, our study of knowledge hinges greatly on the concept that truth is something that can be defined - truth exists as an objective fact.

In light of this, reflect as to why it might be important to understand our relationship to knowledge and where it is derived. Are there questions that effectively determine truth from falsehood?

Decide on two or three questions that seem to be the most effective in determining truth from falsehood in any given framework. Support your reasoning.

ACTION

Defining Epistemology

In brief, Epistemology is the study of knowledge.

In greater depth, Epistemology is the branch of Philosophy that studies the nature and extent of knowledge, truth, and justified belief. It seeks to answer two things: what is knowledge, and “how do we know what we know?”

| The Nature of Knowledge | The Extent of Human Knowledge |

|---|---|

|

|

How we obtain this knowledge is a central problem in epistemology. Is knowledge something that is innate(definition:Innatism is a philosophical and epistemological doctrine that holds that the mind is born with ideas/knowledge. Therefore, the mind is not simply a "blank slate" at birth. It asserts that not all knowledge is gained from experience and the senses.), or is it something that we experience through direct contact or sense-perception(definition:Any of the faculties of sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch, by which the body perceives an external stimulus.)?

The Problem with Perception and Reliability

David Hume, like other noted empiricists such as Locke and Berkeley, believed strongly in a rigorous standard for knowledge. According to Hume, there was no such thing as innate ideas - all knowledge comes from experience.

Going one step further, Hume insisted that there was a problem with perception and taking the notion of causation(definition:The relationship between cause and effect.) for granted. Automatically assuming a cause and effect relationship was not a reliable standard for knowledge.

Hume referred to this as the ‘Problem of Induction.’

In short, Hume suggests that, just because an event, ‘B,’ always seems to occur after event, ‘A’, this does not necessarily mean that the two events are conjoined. Just because, in our previous experiences, B is perceived to always occur in conjunction with A, does not necessarily mean that such a cause and effect relationship is always going to happen. To make such an assumption is not reasonable and justifiable because it is based on an inference(definition:The process of arriving at some conclusion that, though it is not logically derivable from the assumed premises, possesses some degree of probability relative to the premises.). For example, if you walked into your classroom and your teacher asks you to take out a pencil and hands out a sheet of paper, you could infer that you are about to write a surprise quiz - it is also just as likely they could also you to draw a self-portrait, write a letter to your MP or brainstorm ideas for a better mousetrap!

We know that our senses do not always perceive the world as it really is; our senses can play tricks with us. Should we automatically attest to something being true, simply because we perceive a situation to be so; or because in our personal experience that has always been so?

So, while empiricism is the theory that the origin of all knowledge is sense experience, Hume does not want us to automatically jump to a conclusion based on experience without really looking at the evidence.

Other empiricists support this recommendation for caution. Locke, for instance, argued that the only knowledge humans can have is a posteriori - knowledge based on experience. Locke allowed for two distinct types of experience.

| Outer Experience | Inner Experience |

|---|---|

| Outer experience, or sensation, provides us with ideas from the traditional five senses. For example, we see the colour red, we hear the sound of a piano, we touch a fleece blanket, we taste the bitterness of black coffee. | Inner experience, or reflection, is slightly more complicated as the human mind is incredibly active. Our minds are constantly performing operations: examining, comparing, and combining different ideas in a number of different ways to produce knowledge. |

| The Problem with Perception and Reliability | The Problem with Perception and Reliability |

| Of course, one still has to consider the problem with perception. For example, what if one was colourblind? How would your perception of ‘red’ be different from another person without color blindness? What if you don’t like the taste of coffee? How do the differences in perception affect your knowledge based on your experiences? |

The problem with our active minds is that often knowledge based on real experiences can produce knowledge based on perceived or imagined events. For example, we ‘remember’ events from our past - but memory is not always reliable. We ‘imagine’ events in the future based on past, similar events, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that an imagined event is actually going to occur. We ‘desire’ a particular object based on previous needs or wants without knowing if such a thing will produce the same sensation of pleasure. And, we can express ‘doubt’ about a particular outcome because of a perceived, but unsubstantiated, pattern of cause and effect. |

Seeing is Believing?

Another empiricist, George Berkeley believed at all physical objects are composed of ideas - esse est percipi - to be is to be perceived. His position was to defend two metaphysical theses:

- Idealism - the claim that everything that exists either is a mind, or depends on a mind for its existence; and

- Materialism - the claim that matter does not exist.

An obvious objection to Berkeley’s reliance on perception is that it suggests that real things are no different from imaginary ones. If everything exists in our minds, then what of the things we ‘see’ in our dreams or during hallucinations? Certainly, we feel that we are experiencing them, we may even ‘see’ them, but does that mean that we can trust those experiences?

Berkeley countered this by pointing out that yes, while dreams and hallucinations may be perceived as real, we know they are not as they do not exist beyond our involuntary thoughts.

Rationalism

Contrary to Empiricism is Rationalism - the epistemological view that at least some human knowledge is gained a priori(definition:Knowledge that is held, prior to observation. Justification of a belief emerges from pure thought or reason, rather than from direct experience.), or prior to experience.

Rationalists, such as Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, argue that there are some truths that are beyond perception and experience - that there are concepts and knowledge that can only be gained through reason and logic.

|

Descartes and the Cartesian Approach |

René Descartes believed that knowledge of eternal truths, such at mathematics, innate ideas of mind, matter, and God, could be attained by reason alone, without the need for any sensory experience. Even though Cartesians developed probable scientific theories from observation and experiment, they also accepted that science could not prove everything. Human intellect was finite, they contended, but God’s intellect was infinite and omnipotent. |

|---|---|

|

Spinoza and the Notion of Absolute Substance |

Expanding on Descartes’ basic principles, Spinoza’s rationalist theory relied on his notion that God is the only absolute substance. Spinoza was a substance monist - He believed that everything is essentially one ‘thing’ or ‘substance’ composed of thought and extension. All aspects of the natural world are modes of the eternal substance of God, and therefore, can be known through pure thought or reason. Spinoza claims that, as humans are just a mode of this substance, we can affirm the truth inherent within all of reality through different types of knowledge, imagination, intuition, and the exercise of the intellect. |

|

Leibniz and the Notion of Monads |

Leibniz attempted to rectify what he saw as some of the problems that were not settled in Descartes’ dualism by combining Descartes' work with Aristotle's notion of form.

|

Finding a Middle Road: Kant’s Synthesis and His Transcendental Idealism

Kant is generally considered to be the first philosopher who synthesized early modern rationalism and empiricism. While it has been argued that what Kant was really trying to do was find a middle road between dogmatic(definition:The expression of an opinion or belief as if it were a fact. Dogmatism was an early 17th century philosophy based on a priori assumptions.) and skeptical(definition:Relating to the theory that certain knowledge is impossible. Skepticism is generally any questioning attitude or doubt towards one or more items of putative knowledge or belief. It is often directed at issues related to morality, religion, or knowledge.) traditions, his synthesis was widely influential to subsequent discussions on knowledge and truth.

Kant claimed that our senses deliver data which informs our a priori understanding. The idea is that we cannot know anything about the real world - things as they really are - beyond the scope of our understanding. We can only know the phenomenal world, and that world is neither totally independent from the knower, nor entirely the creation of the knower. The phenomenal world is a combination of sense perceptions as they are organized by the a priori categories of the knower.

For example, space and time are only subjective forms of human intuition that would not subsist in themselves if one were to abstract them from all subjective conditions of human intuition. Reality, according to Kant, exists independently outside the human mind. This thesis is what Kant called ‘transcendental idealism.’

Tensions Between Knowledge, Perception, and Experience

As you can see, there is a great deal of tension between perception, experience, and knowledge.

Where and how we attain our knowledge can widely affect our worldview. If we cannot trust our senses because of our differing modes of perception, then what can we trust? Skepticism about the external world and how we perceive it - and if we are truly perceiving it as it really is - means that knowledge is a problem, not a given.

So how do we rectify our skepticism, or at least come to some way of approaching and understanding the nature of knowledge and how we know what we claim to know?

The Problem of Knowledge

Ultimately Kant’s transcendental idealism caused a great deal of disagreement about what it means to ‘know something.’ He was opposed to Berkeley’s subjective idealism(definition:Subjective idealism, or empirical idealism, is the monistic metaphysical doctrine that only minds and mental contents exist. It entails and is generally identified or associated with immaterialism, the doctrine that material things do not exist.) because that form of idealism denied the existence of things apart from the subject - divine or human - and perceiving them. Kant also distinguished transcendental idealism from transcendental realism(definition:Transcendental realism is a philosophy of science that it views things in terms of how they actually are rather than how they appear to the viewer.), by arguing that the latter mistakenly considers space, time, and objects alike to be real in themselves, quite independently from the human perception of them. This leaves open the possibility as to whether one’s perceptions, or ideas of said objects, truly correspond to the objects at all.

Kant suggested that his transcendental idealism did not make claims it could not sustain about the ultimate reality of things; instead, it left individuals free to make statements about things to the extent they appear to the observer. Our self-awareness comes together with the awareness of the external world around us - thus we are as certain of its existence as we are of our own.

Justified True Belief

The traditional approach to the theory of knowledge comes from Plato and his theory of justified true belief - otherwise known as the JTB theory(definition:Justification - you have reason to believe in something; Truth - since false propositions cannot be known, for something to count as knowledge, it must be actually true; Belief - because one cannot know something in which one does not believe.). The focus here is on propositional(definition:A proposition is something which can be expressed by a declarative sentence, and which purports to describe a fact or a state of affairs - such as ‘dogs are mammals'.) knowledge - using the schema ‘S knows that p’, where ‘S’ stands for the subject who has knowledge and ‘p’ for the proposition that is known, what are the necessary and sufficient conditions for S to know that p?

S knows that p if and only if:

- S believes that p, and

- p is true, and

- S is justified in believing that p.

According to this traditional approach to knowledge:

- false propositions cannot be known, therefore, knowledge requires truth;

- a proposition that S doesn't even believe in can't be a proposition that S knows, therefore, knowledge requires belief;

- S's being correct in believing that p might merely be a matter of luck, therefore, knowledge requires a third element, traditionally identified as ‘justification.’

Thus, if we approach knowledge as JTB: S knows that p if and only if p is true and S is justified in believing that p.

According to this analysis, the three conditions — truth, belief, and justification — are individually necessary and jointly sufficient for knowledge.

Exploring the Justification of Knowledge

A belief is said to be justified if it is based on evidence and reasoning, and knowledge based on a justified belief should, logically, be sound. However, as with everything we have studied thus far in Philosophy, there is always room for disagreement.

Humans are fallible, and as such, fallibilism(definition:Fallibilism is the epistemological thesis that no belief (theory, view, thesis, and so on) can ever be rationally supported or justified in a conclusive way. Always, there remains a possible doubt as to the truth of the belief.) counters justification by stating that it is possible to have knowledge even when one's true belief might turn out to be false.

The issue here is the term ‘justification’ and how that can be interpreted and defined.

Defining ‘Justification’

|

Evidentialism |

Evidentialism is a thesis about epistemic justification, primarily - what does it take for one to believe justifiably or reasonably? |

|---|---|

|

Reliabilism |

There are good and bad ways to go about forming beliefs. According to reliabilism, a belief is justified based on how it is formed, and whether that is considered a reliable method of formation. That method can change, depending on what belief-forming mechanisms are likely to be true. So, if perception is considered a reliable belief-forming mechanism, then beliefs based on perception are justified. |

|

Infallibilism |

Infallibilism is the epistemological position that knowledge is, by definition, a true belief which cannot be rationally doubted. Moreover, a belief must not only be true and justified, but the justification of the belief must demonstrate that the belief is incapable of being untrue. |

|

The Gettier Problem |

In 1963, Edmund Gettier published a widely influential article which has shaped much subsequent work in epistemology. Gettier provided examples in which someone had a true and justified belief, but in which we seem to want to deny that the individual has knowledge, because luck still seems to play a role in this belief having turned out to be true. The example he used to illustrate this is as follows:

|

How Do We Know What We Know?

Not everyone knows everything; but how do we go about determining what it is that we know? How do we gain knowledge about knowing?

Leaving out individual specifics, Philosophers look to general ways and means of coming to know a specific fact or truth.

- Some or all knowledge is innate (and is then remembered later, during life).

- Some or all knowledge is observational.

- Some or all knowledge is non-observational, attained by thought alone.

- Some or all knowledge is partly observational and partly not — attained at once by observing and thinking.

Ways of Knowing

|

Innate Knowledge |

The doctrine of Innatism holds that the human mind is born with ideas or knowledge - that the mind is not a “blank slate” at birth. Instead, our inherent nature from birth includes ideas, concepts, categories, knowledge, and principles. Key Proponents: Plato, Descartes, Chomsky |

|---|---|

|

Observational Knowledge |

According to classical empiricist(definition:According to empiricists, our learning is based on our observations and perception; knowledge is not possible without experience.) doctrine, knowledge can only be gained a posteriori(definition:Reasoning or knowledge that proceeds from observations or experiences.). Matters of facts and existence can only be supported if they are made from observation, memory, or inferences (whose premises were ultimately supplied by observation or memory). Key Proponents: Kant, Avicenna, Locke |

|

Knowing Purely by Thinking |

When philosophers ask about the possibility of knowledge being gained purely by thinking — by reflection rather than observation — they are wondering whether a priori(definition:Reasoning or knowledge that proceeds from theoretical deduction rather than from observation or experience.) knowledge is possible. The proponents of such a concept are known as rationalists(definition:A person who believes that reason rather than experience is the foundation of certainty in knowledge.).

Key Proponents: Kant, Spinoza, Descartes |

|

Knowing by Thinking-Plus-Observing |

Possibly, there are philosophical limits upon the effectiveness of observation by itself and of reason by itself - so, what if we combined them? One would act as the cross-check for the other, or at least make us more mindful of our thinking process (thinking about your thinking). The only downside is that if either observation or reflection has limitations, or is flawed, their combination might compound the weaknesses of fallibility of the knowledge. Key Proponents: Behaviourism |

Summarize and Assess: Truth and Knowledge in Everyday Life

Summarize and Assess: Truth and Knowledge in Everyday Life

From a philosophical position, as well as a personal position, we like to think that our knowledge is credible. How do we ensure that our beliefs are justified in truth?

While we are still in the early stages of our study of knowledge, we have enough direct experience with the world around us to begin an investigation into the process by which we attain knowledge. How do the messages, from familial to social constructions, from academia to mass media, influence what we assume is true, justify our system of beliefs, and affect our knowledge of the world?

Your Task:

In this activity, you will create a visual representation - a mind-map, flowchart, or infographic - that demonstrates your understanding of the connections between theories of truth and kinds of knowledge.

Follow the steps below to complete the task:

Step 1: Learn

Familiarize yourself with the following kinds of knowledge. These will form the ‘backbone’ or nodules of your diagram.

Epistemology - How We Gain KnowledgeKinds of Knowledge |

|---|

|

Knowledge by Acquaintance is obtained through a direct causal (experience-based) interaction between a person and the object that person is perceiving. |

|

Knowledge-That is a propositional knowledge and a declarative knowledge. It is the kind of knowledge present whenever there is knowledge of fact or truth. |

|

Knowledge-Wh includes the questions whether, who, why, what and is also a propositional knowledge. |

|

Knowledge-How means knowing how to do and accomplish something. This involves skills or, at least, abilities. |

Step 2: Research

For each of the kinds of knowledge listed above, you will need to find at least two real life examples that illustrate how the theories of truth feed into, and inform, knowledge.

Philosophy of EpistemologyTheories of Truth |

|---|

|

Correspondence The correspondence theory of truth states that the truth or falsity of a statement is determined only by how it relates to the world and whether it accurately describes, or corresponds, with that world. This is as close as we come to "objective" knowledge, and knowledge of objects as “things in themselves.” |

|

Coherence The coherence theory of truth bases the truth of a belief on the degree to which it coheres - or aligns - with all other beliefs in a system of beliefs. One example would be a popular set of beliefs - if everyone else agrees that something is the truth, then it must be so. |

|

Pragmatism A pragmatic theory of truth contends that one cannot conceive of the truth of a belief without also being able to conceive of how, if true, that belief matters in the world. So, for example, if we say that an apple is red, we cannot say that without taking into account what ‘redness’ is, and how that would be understood in relation to other things that could be red, like a balloon or a clown’s nose. The discovery of truth occurs only through interaction with the world. |

For each of the three theories above, you will need to find at least two real life examples that illustrate the theory in practice. These can be examples that you source from a newspaper, a blog, social media, photojournalism, transcripts from interviews, or anecdotal stories. Remember, you are seeking examples of truths in the action or process of informing knowledge. Remember that you need to find examples that you can connect to a specific kind of knowledge in Step 1.

Step 3: Assess and Make Connections

Once you have your examples, assess the information and provide evidence that justifies the connections identified by your responses to the questions. What beliefs would be justified by the type of evidential(definition:Noting, pertaining to, serving as, or based on evidence.) truths that informed the knowledge?

- What connections can be made between the real-life examples of truths or forms of truths that you found, and the way we gain knowledge? For example, are we more willing to accept certains truths if we have direct experience or acquaintance with them? Are there some truths that we are willing to believe, simply because they just seem familiar and they align with our personal biases or perception of the world? Are there some truths we seem unwilling to believe because they are in a form, or from a perspective, that we have previously discredited? Demonstrate the connection by giving one or two specific examples of truths to the kinds of knowledge that they inform.

- How do certain ways of knowing connect to different kinds of knowing? How might that filter what information we are willing to accept as truths? For example, if one believes in innate knowledge, does intuition or a ‘gut feeling’ make us more sceptical to certain messages? Does this mean that certain things ring false to us? At the same time, are certain truths more palpable because we have observed this truth first-hand? Does this mean that perception has an influence on what we will accept or disregard as truth?

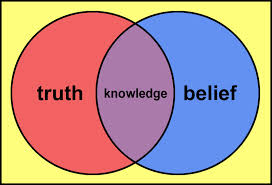

- Much like the Venn diagram presented earlier, for each ‘truth to knowledge’ connection, determine what belief would result, or be the consequence for that particular line of reasoning. Explain how, based on this connection, one would justify a specific system of belief, and what impact this belief would have on one’s worldview. Further to this, in tracing the connection, can you see why an individual should be sceptical of how she/he attained this knowledge? What cautions or counter-arguments should one exercise before accepting any belief as credible?

- In a brief paragraph, summarize your research by presenting your assessment of the connection between truth, knowledge, and belief. According to your research, is there a way to attain knowledge that is preferable to others? Are there forms of knowledge that are superior and more credible? How do we filter out the truths that can adversely impact our knowledge? Why do we accept some truths, and ignore others? How do our personal biases influence the way in which we build knowledge? How do we unpack unjustifiable or entrenched belief systems?

- Objectively speaking, does your research allow you to see your own belief systems and the ways in which you credibly or delusively justify them?

Remember to archive all of your resources as you are required to provide them in APA format with your finished diagram.

Step 4: Create

Remember to cite your sources in APA format.

Your diagram may include an image or visual for each term, but this not required. Do ensure that, visually, you define the connections between the theories, real-world examples, and resulting beliefs, whether through colour, theme, or connecting lines between terms and examples.

CONSOLIDATION

“

Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth.

~ Buddha

How Can We Know Whether We Perceive the World as it Really Is?

In this activity, you had a chance to make connections between truth, knowledge, and belief. Specifically, you explored three conventional knowledge theories and how they justify our beliefs based on that knowledge.

Whether knowledge requires a level of certainty and credibility is an issue that we will explore further in the next activity, but this taps into the ‘politics of knowledge’ - the relationship between the voices of authoritative(definition:) and democratic(definition:Democratic knowledge is collective; it is the knowledge of the masses. It is the truth that we all agree upon - the pervading perspective of what is what in our world.) knowledge.

As you may have seen in some of the examples presented by the class, both voices have issues with credibility. Indeed, if one were to critically analyse the sources of knowledge that exist in the external world - from information transmitted by the media, to the information that we get from family, faith, and academia - one can see how both the authoritative and democratic sources of knowledge may be compromised in our current social and political climate.

So if we can’t believe either voice with unequivocal certainty, how do we know if we are seeing the world as it really is? How can we be sure of our worldview if what informs our knowledge is suspect?