Towards Right Action: Exploring Ethics

Exploring Ethics

MINDS ON

“

Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.

~ Potter Stewart, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from 1958 to 1981.

A Question of Duty

Do you have a duty - an ethical or moral obligation - to always choose to do the “right” thing?

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology, is the normative ethical position that judges the morality of an action based on rules that, in a sense, bind us to a certain set of principles and obligations regardless of the outcome. In essence, it suggests that it is our duty to choose to do the ‘right’ thing, even if it is detrimental to our own self-interests.

In Divine Command Theory, those rules are derived from some form of divine or spiritual commandments or guidelines. Beyond that, in secular deontology theory, the rules, or maxims(definition:Maxims are simple or basic rules that guide action. In Kant’s deontological ethics, maxims are understood as subjective principles of action, such as ‘do not kill,’ or ‘do not steal,’ rules that any reasonable person should agree to.), are based on societal expectations or, in the case of Kantian duty-based ethics, human reason.

The question though is whether that is reasonable.

Should we be expected to make a decision based primarily on a sense of obligation to the greater good rather than what would be preferable to our own well-being and happiness?

An Obligation to Whom?

“

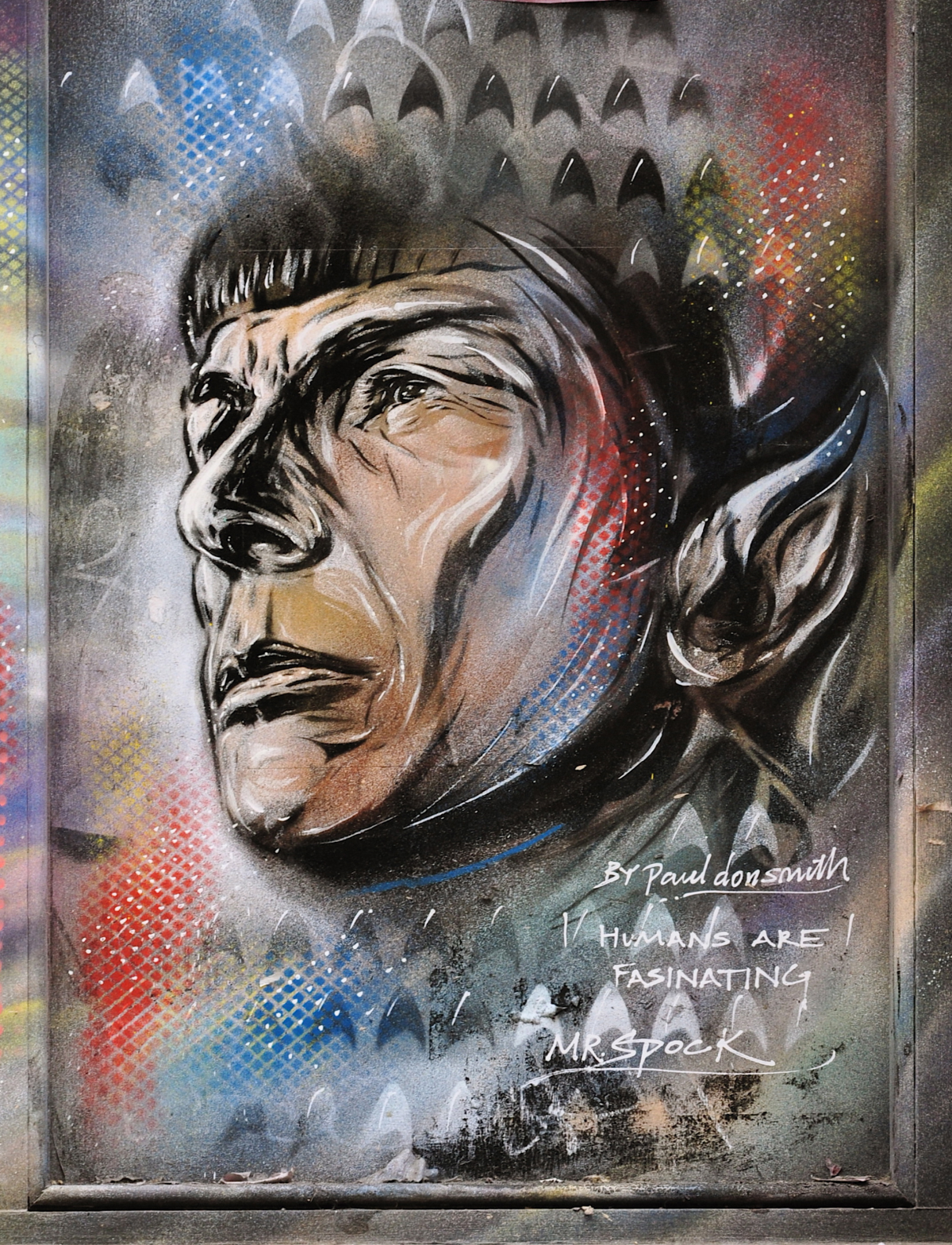

Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.

~ Commanding Officer Spock, The Wrath of Khan (1982)

In the 1982 movie, The Wrath of Khan, the character, Spock, sacrifices his own life to save the starship, Enterprise, and all members of its crew. His reasoning is that the needs of one are not as important as the needs of many, a concept termed ‘act utilitarianism.’

In our society, this principle is quite prevalent. Witness the, “all for one and one for all,” and the, “no ‘i’ in team,” mottos that perpetuate the polite notion that we are somehow all in this together.

Attempt to make a decision that benefits only yourself, especially if it is detrimental to the larger masses, and you will be quickly thought of as ‘selfish,’ ‘inconsiderate,’ and generally, not a good person.

Yet is that a baseless assumption?

Certainly, the moral theory of utilitarianism asserts that each individual should act to serve the greatest good for the greatest number, but why should the benefit of the ‘greatest number’ be deemed more worthy than the rights of the individual? Who made the decision that the one option was the ‘greater good’ than the other?

An assessment of something as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in terms of specific standards or priorities is known as a ‘value judgement,’ and it is one of the reasons that philosopher Ayn Rand used to explain the necessity of Objectivist Ethics - a moral code of rational selfishness as an opposition to the prevailing morality of altruism(definition:The belief in or practice of disinterested and selfless concern for the well-being of others.). Rand points out that ‘selfishness’ is not evil - it is merely concern with one’s own interests, and those interests do not have to be detrimental to another. In other words, looking out for yourself does not mean that your decision is necessarily bad for another. It is not an ‘either/or’ situation - it is merely rational.

An Obligation to Whom

An Obligation to Whom

What do you think? Consider the following questions:

- Are you morally obliged to make a decision that serves others before making a decision that serves yourself? Explain your reasoning.

- Are there specific situations where you should consider your own needs over the needs of those around you? Explain why or why not.

- What informed your response to the first two questions? Explain the logic of adhering to the ‘rules’ that informs your ethical position.

ACTION

What is the Nature of Responsibility?

As noted in the Minds On section, one of the fundamental questions regarding ethics is: to whom do we owe our obligations? Are we more responsible for taking care of our own needs, or are we more responsible for the welfare of others, and in turn, for the betterment of society? From where do these rules regarding our obligations of responsibility come?

Theories About Responsibility

|

The Social Contract

|

The Social Contract theory is the view that a person's moral and/or political obligations are dependent upon an unwritten but understood contract or agreement between her/him, and the society in which she/he lives. For example, if you benefit from the advantages of living within a community, such as having paved roads, publicly-funded police, and fire services, then it is expected that you will abide by the local laws and regulations regarding the use of such services. Key Proponents: Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. |

|

Deontology |

Deontology asserts that we are morally obligated to act in accordance with a certain set of principles and rules regardless of outcome. Deontology can be divided into two branches, religious and secular. Deontological theories hold that some acts are always wrong, even if the act leads to an admirable outcome. Actions in deontology are always judged independently of their outcome. An act can be morally bad but may unintentionally lead to a favorable outcome - for example, shooting an intruder would be bad, but if it saves your family, then ultimately, that act is good. Key Proponents: Immanuel Kant. |

|

Utilitarianism |

The fundamental principle of utilitarianism is that the rightness and wrongness of an action is dependant on the number of people who would benefit from that action. The greater the number of people who would benefit from an action taken, the more ‘right’ it is, even if a small minority is made to suffer or is harmed in some way. Key Proponents: Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill. |

|

Buddhist Ethics |

Buddhist ethics are focused on the goal of keeping “the Middle Way,” cultivating a life of contemplation and enlightenment. Buddhism emphasizes avoidance and moderation rather than striving for any purpose, whether desirable or not. The dhamma (or law) is the foundation and the ‘moral point of view’ around which all else turns. It includes the duties, rights, laws, and virtues, necessary to adhere to the ‘right way of living’ in accordance to rta - the order which makes life and the universe possible. Actions taken that contribute to the rta, are right actions. |

|

The Analects |

The Analects is a collection of sayings and ideas attributed to the Chinese philosopher, Confucius. Its ethics assume that human nature is not intrinsically good or evil but is driven by a desire to become a (morally) “superior person.” This is done by practising the virtues ofren (humaneness), zhong (loyalty to heart and conscience), and li (social propriety or ritual). Any decision or action that contributes to a more virtuous way of being is the right path. |

|

Consequentialism |

Otherwise known as teleological ethics, Consequentialism tells us we need to take into account the final consequence of our action, even if the act itself is not morally good. Let’s say you took an action that was not morally right at that time. If, in the end, the result produced a good outcome, then the consequences outweigh all other considerations. One way to think of this is the old saying, “The ends justify the means.” Key Proponents: Elizabeth Anscombe |

|

Divine Command Ethics |

Divine Command Ethics is a subset of Deontological ethics that includes Judaic, Christian, Zoroastrian and Islamic traditions, as well. It is a theory that considers that “right,” “wrong,” and “obligation” are decided by asking whether actions are compatible with or contrary to the commands of a loving God. Key Proponents: Emile Durkheim, Plato, Aquinas, Averroes, St. Augustine, Von Bingen, Al Kindi |

|

Determinism |

Determinism comes from Christian theology. It argues that if there is a God, then, by definition, He is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-controlling, since He both created everything in the universe and causes everything to happen according to His will. In addition, He created all human beings - every molecule in their bodies - and every force that would ever act upon them. Therefore, however we may feel about making choices, it is really not a matter of choice at all; God controls everything. Key Proponents: John Calvin |

|

Nihilism |

Nihilism is a viewpoint that traditional values and beliefs are unfounded and that existence is senseless and useless. Ethical nihilism rejects the possibility of absolute moral or ethical values. ‘Good’ and ‘bad’ are vague and subjective values that are the result of nothing more than social constructs. Ultimately, do as you wish, it is all inconsequential in the end. Key Proponents: Friedrich Nietzsche |

|

Hedonism |

Hedonism is the philosophy that pleasure is the only good in life, and pain is the only evil. Given this, our life's goal should be to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. According to ethical hedonism, people have the right to do everything in their power to achieve the greatest amount of pleasure possible to them. Key Proponents: Aristippus of Cyrene, Epicurus. |

|

Objectivism |

Objectivism is the philosophy of rational individualism founded by Ayn Rand. Objectivism advocates the virtues of rational self-interest—virtues such as independent thinking, productiveness, justice, honesty, and self-responsibility. What is ‘good’ is that which supports and promotes an individual’s life. Key Proponents: Ayn Rand |

|

Altruism |

Altruism - or Ethical Altruism - is the selfless concern for the welfare of others. It proposes that individuals have a moral obligation to help, serve, or benefit others, if necessary, at the sacrifice of self interest. In other words, an action is morally right if the consequences of that action are more favourable than unfavourable to everyone else, except the individual doing it. Key Proponent: Max Scheler, Aquinas, Rabia al-Adawiyya, Auguste Comte, Buddhism. |

CONSOLIDATION

“

You are personally responsible for becoming a more ethical society than the society you grew up in.

~ Eliezer Yudkowsky, American AI researcher and writer best known for popularising the idea of friendly artificial intelligence.

Are the Rules Relative?

Relativism is the view that ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ ‘right’ and ‘wrong,’ and all standards of reasoning and judgement used to assess such questions, are subject to the authority of the context giving rise to them. In essence, relativism recognizes a diversity of contexts.

For example, we, as outsiders to a culture, cannot accurately judge whether an ethical decision is ‘bad’ or ‘good’ because we may not have the same perspective or understanding as those who made that decision. What is ‘right’ for us, may not be ‘right’ for someone else. This is also known as the ‘principle of tolerance,’ where all ethnocentrism(definition:The belief in the superiority of one's own cultural group.) is abolished, and we exist in a society in which all traditions are given equal rights.

As you can imagine, such a viewpoint can make the determination of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ problematic. While on one hand, relativism promotes a sense of tolerance and open-mindedness, especially in a post-colonial worldview, detractors also dismiss relativism for what they see as “intellectual permissiveness” - allowing for any action to be acceptable if framed in a favourable context. Detractors maintain that, if everything is a matter of perspective, then ultimately, there are no unethical decisions.

To get a better understanding of the different types of relativism, and the possible drawbacks of these viewpoints, look at the following interactive learning object:

FormsofRelativism

As with many things, there are pros and cons with relativism:

Pros:

- It allows for a greater understanding of other cultures.

- Avoids unacceptable consequences of "fixing" other cultures.

- Flexible - many ethical theories developed, one is not completely "right."

Cons:

- Implies that we are not allowed to evaluate/criticize problematic practices, such as sexism, racism, homophobia - due to differing attitudes.

- Slippery slope argument - can be seen as one step away from subjectivism(definition:A theory that states that all knowledge is subjective.).

- Morality is reduced to a social nicety; there is little reason to be moral other than to fit in.

Philosopher’s Notebook: What If It is All Relative?

Philosopher’s Notebook: What If It is All Relative?

In your notebook, respond to one of the following prompts:

- Does the existence of several ethical and/or moral viewpoints mean that there really is no true definition of ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ ‘right’ or ‘wrong?’

- Is there a way to argue with another person’s moral perspective without offending her/him? Should we even attempt to, even if we feel strongly that a given action is morally and/or ethical reprehensible?

Make sure you archive your entry as you may be asked to revisit it in another activity.