Liberty, Fraternity and Freedom: Exploring Social and Political Philosophy

The Social Contract

MINDS ON

“

The social pact, far from destroying natural equality, substitutes, on the contrary, a moral and lawful equality for whatever physical inequality that nature may have imposed on mankind; so that however unequal in strength and intelligence, men become equal by covenant and by right.

~ Jean-Jacques Rousseau

A New Society!

President Musk has put a call out to some of the brightest, most innovative thinkers around the world. After several decades, the latest attempt to terraform a small portion of Mars has finally succeeded, and now it is time to colonize the planet - our Earth II!

But before the mass immigration can begin, some decisions have to be made about the new society. This is a planet in its infancy - the society that we were used to on Earth: its infrastructure, its economies, even its social order - these things do not exist on this distant new home. Indeed, at this point, there are not even countries - just this one, massive outpost!

And for all that, this outpost won’t hold everyone - some people will have to settle in the more inhospitable parts of the planet, growing potatoes and recycling their own waste water. As we said, terraforming has only just been successful on a small portion of the planet. What Mars needs is pioneers! People willing to sweat it out and struggle - for a few generations - before the whole planet is transformed from red deserts to green oases!

Of course, no one wants a repeat of the mistakes from the past, so President Musk wants a global team of experts to carefully construct a new, just society.

To achieve this aim, he has asked the experts to make the BIG choices about this new society. These are tough choices about justice and rights, distribution of wealth, access to resources such as jobs, education, health care - basically the rules that will govern Earth II.

The one catch? Whatever choices the committee makes, its members will have no guarantee of the position they will each have in this new society.

For instance, suppose the committee decides that, since the planet is still terraforming, it is not possible for everyone to live in the completed outpost. So 50% of the society will be denied certain rights as to where they can settle on this new planet: they must settle in the more inhospitable areas. If the committee decides that this is a just ruling for the greater good of Earth II, then it makes this ruling with no guarantee that its members, their children, and successive generations, will not be part of that 50% sent to toil away on the fringes of this new civilization.

So, knowing that there is a 50% chance that a punitive, unfair, or unjust ruling may affect them, how do you think this will have an impact on the decisions the committee makes about the new social order of Earth II?

Rulings and Rights, Without Exception

Rulings and Rights, Without Exception

Under the Canadian Charter of Rights, if you are a Canadian citizen, your rights include the following.

- Democratic rights (for example, the right to vote)

- Language rights

- Equality rights

- Legal rights

- Mobility rights

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of expression

- Freedom of assembly and association

If, like the imagined committee for the colonization of Mars, you were required to make decisions about the rules and rights for all, which five of these rights do you propose should be given, without exception, to all citizens?

Present your five choices and your reasoning to support these choices. You should be able to explain and defend your choices.

ACTION

John Rawls and a Theory of Justice

In many ways, we are biased by our own situations - we tend to see the world from our present position. This contributes significantly to our ‘worldview.’ So when asked to make decisions on rules that could be unfair or unfavourable to a particular segment of a population, we make those decisions with an instinctual sense that we are not in the group that is about to be adversely affected.

Let’s face it, when given a choice, most of us will not choose to live a life of hardship and want. If someone has to suffer, it becomes a ‘me or them’ scenario. So how can we agree on a social contract to govern the world if we can only think about bettering our own situation?

In 1971, philosopher John Rawls published, A Theory of Justice, where he suggested that there was only one fair and objective way to make these decisions without identifying with our personal circumstances. He suggested that we should imagine we are sitting behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ that prevents us from knowing who will receive a given distribution of rights, positions, and resources based on the decisions made.

As presented in the Minds On section, if you are unaware of who will be advantaged and/or disadvantaged by a ruling, you are more likely to make a ruling that is equally beneficial to all sides. Personal considerations and morally irrelevant justifications for inequalities are made obsolete as people seek social cooperation for fear of being on the losing side of a decision.

Think of it like slicing a piece of cake.

The protocol is as follows: one person ("the cutter") cuts the cake into two pieces; the other person ("the chooser") chooses one of the pieces; the cutter receives the remaining piece.

Simple, right?

There is an incentive for the cutter to divide the cake as equally and fairly as possible so both people benefit, plus, by allowing the chooser first choice, there is an inherent weight of responsibility here. Even if the cake is divided slightly unevenly, the chooser has been given an opportunity to take the better half, and does not. If she or he feels cheated, this person has only herself or himself to blame.

This is known as the ‘divide and choose’ procedure.

Further to this, Rawls provided two primary principles to supplement the veil of ignorance: the ‘liberty principle’ and the ‘difference principle.’

According to the liberty principle, the social contract should try to ensure that everyone enjoys the maximum liberty possible without intruding upon the freedom of others - the social contract should guarantee that everyone has an equal opportunity to prosper. But if there are, for any reason, any social or economic differences in the social contract, those who are in an advantageous position should help those who are worse off. This is the difference principle.

Thus, by applying all aspects of Rawls's Theory of Justice, we can ensure that we structure rules in our society that are fair and just for all.

Revisiting Hobbes, Locke and the Social Contract

Of course, what Rawls proposed is not a new idea.

While the concept of a social contract had been around since the time of Socrates, the modern expression of the theory begins with the English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes.

Hobbes' theory of government is set out in in his 1651 publication, Leviathan. It challenged two predominately held views of government authority at that time:

- that the authority of kings is derived from God, the so-called, ‘Divine Right;’

- that a king's power should be absolute, as it comes from God.

Instead, Hobbes argued that government existed for the benefit of the people and derived authority from the collective - it is the people who give the government power over them. Hobbes believed that people were born free, but that human nature was inherently selfish and greedy. Left to their own devices, humans would only look out for themselves.

You may recall similar discussions we had on this topic of human nature in the Minds On section of Activity 1 - Hobbes referred to this as the ‘state of war’ - a way of life that he proclaimed was certain to prove "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." (Leviathan I).

Hobbes proposed that once humans realized that a society with no order or rules was detrimental to their self-preservation, they would naturally seek to unite in a network of mutually beneficial agreements or contracts to overcome the perils of their natural state.

This now united collective, Hobbes named a ‘leviathan.’ He viewed it as a single entity, a new ‘whole.’ And who should make decisions for this new ‘entity?’ Someone in a position of authority - a sovereign. Thus, to save themselves from themselves, the leviathan enters into a commonwealth - a binding contract to a sovereign authority - trading its liberty for peace.

In contrast, John Locke believed that personal liberty was given to all by God, and that no one, let alone the state, should have complete, irreversible control over it.

Like Hobbes, Locke also believed in the Law of Nature; however, he argued that humans were not greedy and selfish by nature. That being said, conflict could arise if one person tried to deprive another person of liberty or property. So, like Hobbes, Locke also agreed that people would come together to form states - to protect individuals and to provide peace. And yes, certainly, if a member of society broke the rules set by the state, she or he would be punished. But unlike Hobbes, who believed that it would be better to live under the rule of a bad sovereign, rather than risk returning to the ‘state of war’ that is humankind in its natural state, Locke believed that if a state did not live up to its side of the social contract, then the people had the right to punish it. Indeed, Locke felt that it was a moral obligation for people to rebel against a tyrannical government and its unjust laws!

In his Two Treatises on Government published in 1690, Locke put forth the notion of a “right to rebel” - that governments exist, “by the people, for the people.”

In short, the government holds power only because the people consent to be governed by it.

It is this notion that became widely influential in both the American and French Revolutions, and is the foundation of modern liberal democracy.

Protection or Intrusion?

One of the fundamental concepts of social contract theory is that individuals give up some of the freedom and liberty they would enjoy in the state of nature, and trade it for the stability and security offered by an organized society. Anyone who then enjoys the benefits of the social contract is a party to it, whether or not she or he explicitly or tacitly agreed to it. The contract is not something you can opt out of; it is binding and permanent.

However, as we just read, there has been some controversy about the limits of this contract. For example, Hobbes and Locke were certainly not in agreement on how much liberty and obedience the public owed the state (in Activity 3, we will follow this thread regarding civil disobedience further with Rousseau and Thoreau).

Certainly both felt that people were better off in society, being able to enjoy their lives and goods without living in constant fear, even if they had to agree to obey rules - even ones that might at times seem constrictive or detrimental to their self-interest.

But what are the just limits of state authority? And what are the limits of the individual's rights and responsibilities under the social contract?

The debate between those who believe the state should play a greater role in the life of the individual and those who believe it should play a lesser role has been very much central to Western political philosophy since the American and French revolutions, as well as throughout the twentieth century. Indeed, it is this debate that first initiated Rawls’ A Theory of Justice.

According to Rawls, society is composed of “atomistic individuals,” people who make decision for themselves, but with an understanding that a just society requires that they consider the rights and needs of others. This requires the provision of social welfare measures, and a redistribution of property to make society more egalitarian(definition:A belief in the equality of all people, especially in political, economic, or social life.).

As expected, there is backlash to Rawls’ ideas. There have been accusations of liberalism, socialism, and the formation of a welfare state or ‘nanny state,’ where the government is regarded as overprotective and interferes too much in the daily lives of its people.

In Robert Nozick’s, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, he argued instead for a ‘night watchman state.’ According to Nozick, the limits of the state should be the provision of a military, the police, and the courts - just enough to protect people from aggression against their persons and property - but not so little that we slip into anarchy. Such a minimalist state, minarchists(definition:A libertarian position that proposes that the only legitimate governmental institutions are the military, police, and courts.) say, would provide a political system that truly respects the fundamental rights of the individual.

The Social Contract

We are born and already members of the state under the social contract. Is this, perhaps, one reason why we give it very little thought until we find ourselves in a position or situation to question the legitimacy of the state’s authority over the individual?

In times of great strife or want, we may question if the state is doing too little, is acting justly, or is overstepping a boundary. On the other hand, we tend to have the same concerns even in times of great joy and celebration, such as questioning the use of “taxpayer dollars” for what some may consider frivolous or a waste.

Look around you - there are probably several examples of the social contract in progress:

- from the street lights at the end of the road to the after hours walk-in clinic in your community;

- from attending your place of worship openly to giving your seat on the subway to an elderly person;

- from having unfettered access to social media to the freedom to march in a peaceful protest.

These are all examples of the social contract in Canada.

On the other hand, we can also have the following situations:

- from the panhandler on the street to the unfilled potholes in the road;

- from the lack of affordable housing to the crumbling infrastructure;

- from the lines outside the local foodbank to the posted flyers calling out for people to come together and demand action.

These, too, are all examples of the social contract in Canada.

The Social Contract

The Social Contract

Seek out examples of the social contract in your own community. Whether the focus is optimistic or pessimistic, supportive or critical, your aim is to visually represent a particular philosophical viewpoint of the social contract.

To review, in this activity we explored the theories of:

- Rawls;

- Hobbes;

- Locke; and

- Nozick.

Feel free to represent the theories and viewpoints of one of these four philosophers.

You may also wish to focus on a particular aspect of the social contract, such as one of the following themes:

- Rules and Laws;

- Authority and Civil Disobedience;

- Secular and Religious;

- Public and Private;

- Freedom;

- Liberty;

- Citizenship;

- (In)Equality;

- Justice;

- Fairness;

- Hegemony;

- Colonialism; or

- an alternate choice.

Step 1:

Choose one philosopher’s theories, or one philosophical viewpoint, to represent. Do some additional research beyond this unit to fully understand the nuances that may not have been discussed here. At the same time, begin to look around you and discern the explicit and implicit ways the social contract is present. This could be in street art, murals, posters, graffiti, signage, window displays, infrastructure, architecture, public spaces, statues, and/or people. Look for a theme amongst the elements - it could be plainly obvious, or you may have to dig deeper and make connections.

Step 2:

Record five to eight examples found within your community. When selecting each of your examples, consider the following questions.

- How does it represent the theories or viewpoint of your selected philosopher/philosophy?

- How does it fit within your worldview of the social contract?

- How does it represent the theme you intend to convey?

Step 3:

Deconstruct the items/elements (individually or collectively). Whether your viewpoint is optimistic or pessimistic, these elements must demonstrate that the social contract is present within your community.

Below are some relevant questions that you could ask yourself during this step:

- What is it about these particular items/elements that you personally feel represents your understanding of, and viewpoint about, the social contract?

- Would someone viewing your visual essay understand what you are seeing and what you are trying to say - or will she/he need an explanation to accompany the visual essay?

- What is the overall message of these items/elements when placed collectively in the visual essay? Is your message inherent? Or is it your interpretation of the items/elements that gives them a collective meaning?

- Are the items/elements an expression of truth or opinion?

- What perspective or worldview is necessary for the audience to fully understand the meaning of these items/elements? In addition, how would the meaning be effectively conveyed to those who are not connected to the same/similar perspective or worldview?

- Could your experience or interpretation of these items/elements be wrong? Be prepared to explain how your own worldview may be a factor in your deconstruction and understanding.

CONSOLIDATION

“

Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore, and even deny anything that doesn't fit in with the core belief.

~ Frantz Fanon, Philosopher and Revolutionary

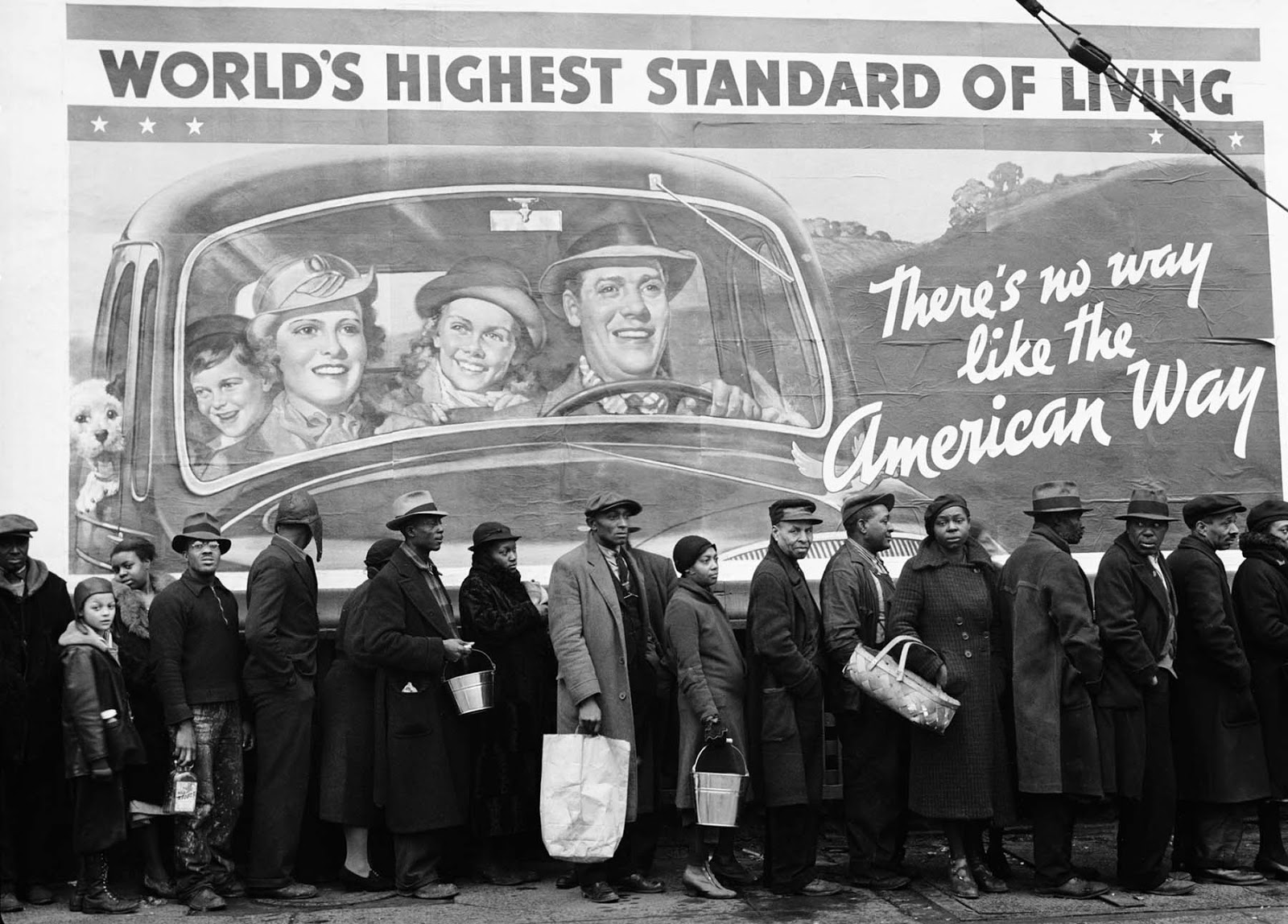

Exploring Hegemony

A ‘hegemony’ is the social, cultural, ideological, or economic influence exerted by a dominant group in any given society. Furthermore, it involves the value systems, social norms, and mores by which a dominant culture maintains its dominant position.

Hegemonies are what we use to smooth out the inconsistencies in our society. For example, if we talk about the ‘freedom of the press,’ ‘no one being above the law,’ and ‘presumed innocence,’ we see examples of these principles being transgressed all the time. A celebrity acts out in an antisocial manner and instead of taking ownership for his or her behaviour, the press is manipulated into garnering public sympathy for this individual. A CEO commits fraud, and rather than call it what it is - theft - it is called “white collar crime;” said CEO then escapes severe punishment. A person of colour walks down a suburban street and is racially profiled by the police. All of these are examples of hegemony, and while we know that these acts are inconsistent with the social contract, for some reason we are hesitant to target them.

We need to ask ourselves why that is. When confronted with hegemony in society, why do we often engage in cognitive dissonance(definition:The state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioral decisions and attitude change.)?

Take a moment and look at some of the visual essays that your classmates shared. Consider the following questions:

- Were there examples of the social contract that, despite the justification in the author’s explanation, you found difficult to accept?

- Did some of the viewpoints present glaring hegemonies - rules and regulations that made you question the legitimacy of the state’s influence?

- Or, did you push aside your doubts and engage in cognitive dissonance, rather than be in breach of, or point out, the inconsistencies in the rules?