CLN4U

Canadian and International Law

Unit 2: Legal Foundations

Activity 3: Sources of Law

You have been thinking about the questions, “Why do people break the law?” and “Why do people obey the law?” Other important questions to consider include “What is the law?” and “What are the sources of law?”

You are likely familiar with the organization of Canadian law. In order to better understand the law we have classified, or organized it, according to purpose and area of focus. These various areas of law connect to our daily lives and govern many of our activities and interactions. Take a moment to determine the definition of each area of law and then take the quiz to check your understanding.

On the surface, the law appears straightforward. Law is a set of rules that governs the behaviour of citizens. It is usually accompanied by a punishment to “encourage” people to obey the law. For example, in most countries the state authority prohibits taking the life of another human being. This seems to be logical, simple and clearly articulated.

What happens if some of the relevant factors shift?

Consider the following:

Quite quickly you begin to see that applying this law is no longer simple and that it can present a number of challenges. All of these questions that emerge make the study of law appealing and interesting. The study of law is an investigation into the nature of law; its origins and principles, and its application is known as jurisprudence. It is sometimes referred to as the science or philosophy of law.

Is it murder? What do you think?

Is it murder? What do you think?

Think about the scenarios. What do you think? To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Use the following scale:

You have committed murder if:

- You take a life in your role as a soldier fighting for your country.

- You take a life while trying to defend yourself or a loved one.

- You take a life at the request of a person who is seriously ill.

Enrichment

Enrichment

You may wish to read a bit more about jurisprudence here.

Law is:

the system of rules that a particular country or community recognizes as regulating the actions of its members and may enforce by the imposition of penalties.

Jurisprudence is:

a branch of legal philosophy that seeks to analyze, explain, classify, and criticize entire bodies of law.

Roots of Law

What influences have shaped the justice system over time?

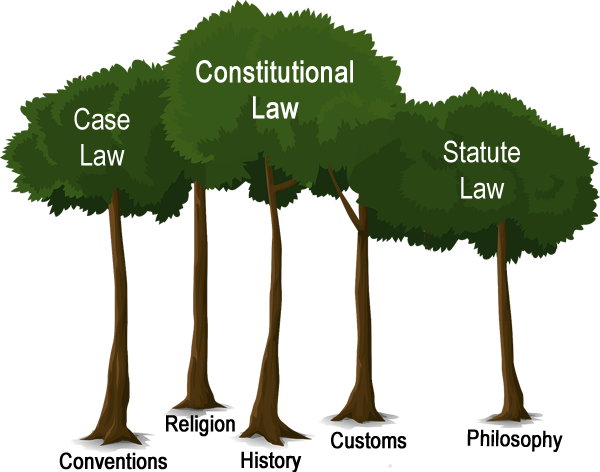

Imagine that the law is the shape of a tree. The roots go down deep into the earth and provide nutrients and water to the tree. Just as the roots of a tree draw their strength from a number of sources, so too does law.

Religion

The influence of religion on law is profound and can be traced back over millennium. Consider two of the Ten Commandments.

"Thou shalt not steal." is referred to in Section 322 of the Criminal Code:

Theft

322 (1) Every one commits theft who fraudulently and without colour of right takes, or fraudulently and without colour of right converts to his use or to the use of another person, anything, whether animate or inanimate, with intent

(a) to deprive, temporarily or absolutely, the owner of it, or a person who has a special property or interest in it, of the thing or of his property or interest in it;

(b) to pledge it or deposit it as security;

(c) to part with it under a condition with respect to its return that the person who parts with it may be unable to perform; or

(d) to deal with it in such a manner that it cannot be restored in the condition in which it was at the time it was taken or converted.

"Thou shalt not bear false witness against your neighbour." is referred to in Section 131 of the Criminal Code:

Perjury

131 (1) Subject to subsection (3), every one commits perjury who, with intent to mislead, makes before a person who is authorized by law to permit it to be made before him a false statement under oath or solemn affirmation, by affidavit, solemn declaration or deposition or orally, knowing that the statement is false.

There are other ways that religion influenced Canadian law. It used to be illegal to shop on Sunday and students in public schools used to recite the Lord’s Prayer each morning. As Canada has become more multicultural and diverse, Canada's laws and policies have changed to recognize Canada's diversity.

Philosophy

Watch this brief video "An Introduction to Legal Theory" presented by Dr. Mohsen Al Attar from Queen’s University in Belfast.

Customs and Conventions

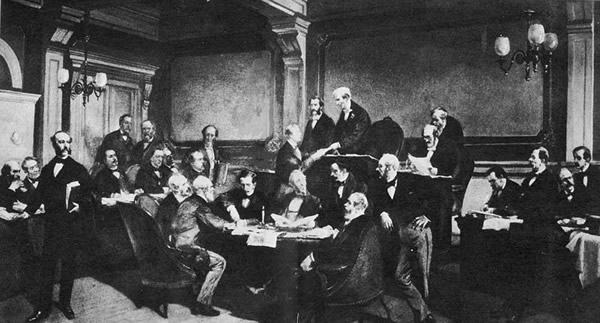

This is a painting of the signing of the First Geneva Convention.

Source: Charles Édouard Armand-Dumaresq [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A custom is a long-standing practice that has been accepted by the community for so long that it has become an unofficial law. Sometimes these customs are formalized into law and sometimes these customs fade away over time. Current territorial boundaries or jurisdictions are sometimes based upon customs. A convention is a more formal agreement that imposes responsibilities upon the involved parties. An example would be the Geneva Conventions which outline acceptable treatment of prisoners of war.

History

Canadian law can trace its roots to very early historical periods as well as more modern times. Scroll over the map below to discover the roots of Canadian law. Humans have contemplated the role of law and the meaning of justice for centuries.

British Legal Tradition

The influence of British law on Canada is evident. The structure of our courts, the roles of judges and the jury as well as key principles have been shaped by British legal tradition. Under the reign of Henry II (1154-1189) the laws of Britain became more unified. Prior to this period, decisions were made by the local lords and the methods of determining guilt or innocence varied widely. In some areas the accused would undergo a physical ordeal or participate in a duel. The belief was that God would be on the side of the righteous or honest person. Under Henry II, travelling judges would hold court in different areas of the country and try to apply the law and make decisions that were common for cases that were alike in nature. For example: The traditions of one area may have dictated that a person who stole the livestock of another person would have to return or reimburse the rightful owner for twice the value of the stolen property whereas in another area, the punishment would be a public lashing. These circuit judges would apply the law in a similar manner for cases that were similar. Using the decisions of the judges or the precedents form the basis of case law. This helps to ensure that the law is predictable, stable and fair. The Latin term for the rule of legal precedent is stare decisis.

Over the years all of these influences have combined to form the content of our law as well as the structure of our legal system. The law is not static however; it has changed and adapted over time.

Statute Law

Laws made through Parliament, known as statute law, have been created in response to the needs of society, developments in technology, domestic or international events, as well as shifting morals and values.

Constitutional Law

Canada has a Constitution which outlines the responsibilities of government and is the highest form of law.

Case Law

As noted above, early British case law formed some of the content of Canadian law. This area of law is continually changing as new case law, or common law, is created by Canadian judges.

Tips

Only you know, if you know!

You may be familiar with the structure of the Canadian parliamentary system and the process through which a bill becomes a law. Perhaps some of the information from earlier classes such as Civics or Grade 11 law has faded over time. If you are in need of a refresher, please check out the Government of Canada website How Parliament works and the Legislative Assembly of Ontario website. You may also wish to watch How Canada became a Democracy and How Canada became a Democracy Part 2. Be sure to be independent and take responsibility to ask questions and seek answers if there are gaps in your understanding.

This brief reading focuses on Making a New Law. You are strongly encouraged to review this material. It will take you approximately 1 hour.As you know, one way laws are created are by our politicians through our federal House of Commons and through each of the provincial legislatures. These laws are created by our federal Members of Parliament (MPs) and our Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs).

Enrichment

Enrichment

For an irreverent view of our system, check out "Rick Mercer's Everything you wanted to know about Canada but were afraid to ask." It was created in 2009. Though the roles of Governor General and Prime Minister are currently held by other people, the clip does contains relevant information and it is presented in an engaging manner.

Precedents

The other way that new laws are created is through our courts with the use of precedent or the common law system. This system relies upon the integrity and unbiased decision making of a judge. He or she plays a particularly important role in our courts. The precedent will be used in future cases that share similar characteristics and a judge is obligated to refer to earlier cases. The decisions made by judges are therefore very important.

For a quick clip that describes the meaning of the concept of precedent please watch the video "How judicial precedent works."

Review the big ideas from the video:

While this video is British, it is important to remember that many aspects of Canadian law stem from British law. The use of precedents is a good example of the close connection between the two systems.

There are many good reasons for using precedents:

- It promotes predictable and consistent development of legal principles.

For example: The Supreme Court may establish a “test” or a way of deciding an issue. This might help to ensure fairness. An example of this might be the Oakes test which determines if a limit on a right or freedom was reasonable. ...more about the Oakes test.The Case of R v Oakes David Edwin Oakes was charged with possession of drugs, and possession with the intent to traffic. At the time of the trial, a person charged with drug possession was automatically charged with possession with the intent to traffic. If a person was found guilty of possession of drugs, s. 8 of the Narcotic Control Act (NCA) (now called the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act) placed the onus on the person charged to prove that there was no intent to traffic. If the accused could not prove lack of intent, the accused would automatically be found guilty of the charge. Mr. Oakes challenged this section of the NCA as an infringement of his s. 11(d) Charter right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. The SCC found that s. 8 of the NCA violated s. 11(d) of the Charter. The Court then considered whether the government could justify this infringement under s. 1 of the Charter. Section 1 requires the government to show that the law in question is a reasonable limit on Charter rights, which can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. The Court found that the government failed to satisfy s. 1 of the Charter, and as a result, held that s. 8 of the NCA was of no force or effect. Ontario Justice Education Network

- It promotes reliance on judicial decisions.

For example: The court may rule in such a way that requires the government to rewrite or amend a law to be in keeping with a verdict. - It limits the power of the judiciary.

For example: A judge may not punish one offender far more harshly than another offender convicted under similar circumstances. Though they have freedom, judges are obliged to use precedents to guide their decisions. - It helps people know what to expect in certain legal situations, etc.

For example: A judge may have ruled that evidence collected in a particular way violated the rights of the accused. The police now have a clearer idea of the rules for collecting evidence to be used in a trial.

There are circumstances under which a decision might go against an earlier precedent. A law may be causing harm; it may be wrong or it may have become difficult to defend over time.

Landmark Cases

Let's look at a few important cases. These are often called “Landmark” cases because they result in legal change; they are particularly important and the verdict impacts many people. Landmark cases are legally significant. These cases often take time to be resolved and many people within the justice community have differing perspectives on the way the law should be interpreted. This is a challenge for judges.

The following summaries are taken from an article written by the Ontario Justice Education Network called Cases that have Changed Society.

Please read each case. As you are reading think about:

- the legal significance of the case.

- one connection you can make to this case either from your introduction to sources to law, to current events or to personal experience and knowledge.

- one question you have about the case or its outcome.

Be prepared to share your thinking. You may wish to use the following organizer to record your thinking.

Tips

Just a reminder for you.

An effective question in legal studies should:

- generate other additional questions;

- lead to more than one possible answer/response;

- link to essential ideas in a discipline;

- connect to a concept of thinking;

- focus upon aspects of the content or evidence under exploration.

Case Study

Aboriginal Title: Delgamuukw v. British Columbia. [1997] 3 S.C.R..1010

The appellant, Gitksan and Wet'suwet'en chiefs, claimed Aboriginal title, or ownership, to 58,000 square kilometres of land in B.C. on behalf of their “houses.” This claim was based on their legal system of property rights and their pre-contact ownership of the land. The Supreme Court of Canada recognized for the first time that First Nations held title to their land prior to European arrival on the continent. The decision discusses the unique nature and characteristics of Aboriginal title. The court decided that that there was not enough evidence to determine if this land was historically owned by the Gitksan and Wet'suwet'en Nations, or whether the Nations had ceded, or given up ownership to the land. However the court did discuss what kind of evidence could be used to establish a land claim. This case creates the legal possibility of a successful claim to Aboriginal title under Canadian law. This case is also notable because it recognizes the importance Aboriginal people attach to oral histories and demonstrates how Canadian legal rules of evidence can accommodate oral histories during trial.

No Means No: R. v. Ewanchuk, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 330

After interviewing a job applicant, Mr. Ewanchuk invited her into his trailer to show her some work. He began to touch her. Each time she said no, he stopped his advances but then soon after he would make an even more intimate advance. Mr. Ewanchuk was charged with sexual assault. He raised the defence of “implied consent,” arguing that although the woman initially said no, she stayed in the trailer and failed to continually object to his advances. The trial judge accepted this defence and acquitted him. The Supreme Court of Canada found “implied consent” is not a defence to sexual assault. The court recognized that an accused may have a defence if there is evidence that the accused had an honest but mistaken belief that someone had consented, but the court will not imply consent. This case is notable for debunking the myths and stereotypes about sexual assault and making clear that people must always establish the clear consent of their sexual partners.

A Duty to Act to Protect Rights: Dunmore v. Ontario (Attorney General) [2001] 3 S.C.R. 1016

Ontario's Labour Relations Act did not allow farm workers to unionize or receive labour protections. Four farm workers and a Union challenged this exclusion as an infringement of their section 2(d) right of association, as well as their rights under s. 15. equality rights. The majority of the Supreme Court of Canada made the unique finding that the freedom to organize may require the government to extend legislative protection to vulnerable groups. Usually the Charter protects rights when the government has acted in a way which violates an individual's rights. When a government has not taken any action (program, legislation etc), it usually cannot be said to have violated any Charter rights. In this case, the court decided that because the farm workers were unable to exercise their collective freedom to assemble without the protection of labour rights, their freedom of association was violated. The government was required to act to protect these rights. This case acknowledges that the Charter may, in some cases, impose a government duty to act in order to protect Charter rights.